welcome to week 1

This is the didactic curriculum for the NEA Baptist Nephrology Rotation. For week one, we’ll be talking about the topics below. Scroll to each topic to find the required reading as well as links to expertly-written articles by renal fellows and academic nephrologists. The first skill you’re going to become amazing at is urine sediment analysis. This is a skill that can take your hospital and clinic evaluations of reduced kidney function from vague diagnoses to in-depth explorations of nephritic disorders and a firm understanding of the pertinent pathophysiology of a patient. Next, we’ll work through the proper evaluation of AKI and provide a good framework for doing so. To end (new best) week (of your life), we’ll discuss hospital management of hypertension.

Table of Contents

How to Spin Urine

AKI Workup

Hospital Management of Hypertension

How To Spin Urine

During the evaluation of AKI, we combine history of the patient with physical exam and laboratory findings. One of the most important aspects of AKI evaluation is examination of the urine sediment. When we refer to urine sediment, we are referring to cells, debris, and other particles present in the urine. There are only a handful of urine sediment findings that we look for on a regular basis. These include casts, red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), crystals, and amorphic debris.

Urine can contain some or all of the above items. In order to increase the chance that we will see some of the aforementioned urinary findings, we concentrate cells and debris in the urine through centrifugation.

To prepare urine for examination under the microscope, get a 5-10mL of a fresh urine sample— two hours old or less if possible. Centrifuge urine at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes. Be sure to appropriately counterweight the urine sample with an equivalent amount of urine to within 0.25mL. Pour out all of the supernatant in a sink. To do this, invert the vial completely and hold for 5-10 seconds. This should leave 2-3 drops of urine in the test tube along with the pellet. At this point, gently tap, shake the tube to resuspend the pellet.

Use a pipette to place 1 drop of urine on a glass slide and cover with a slide cover.

Below are some common urinary findings:

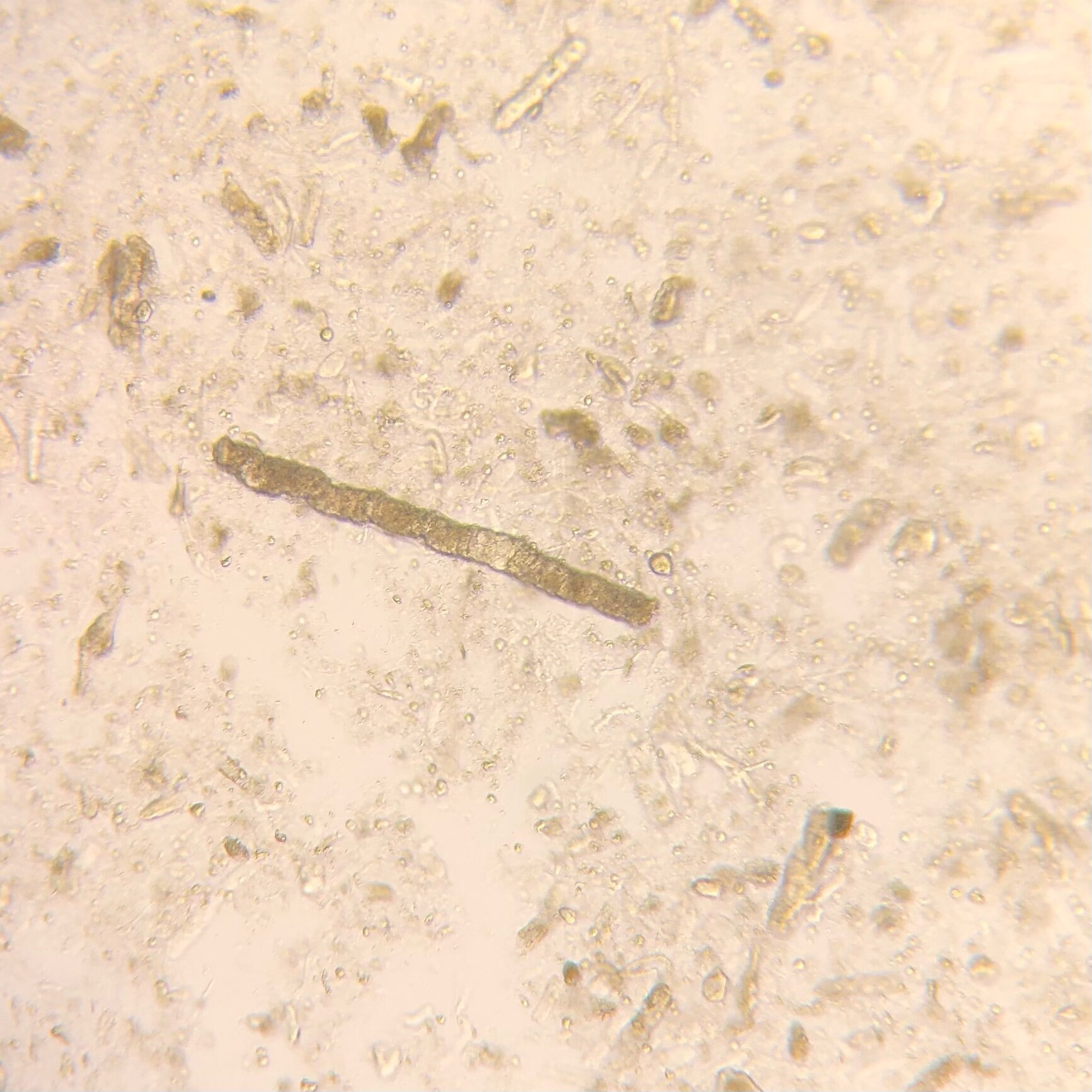

Granular Casts

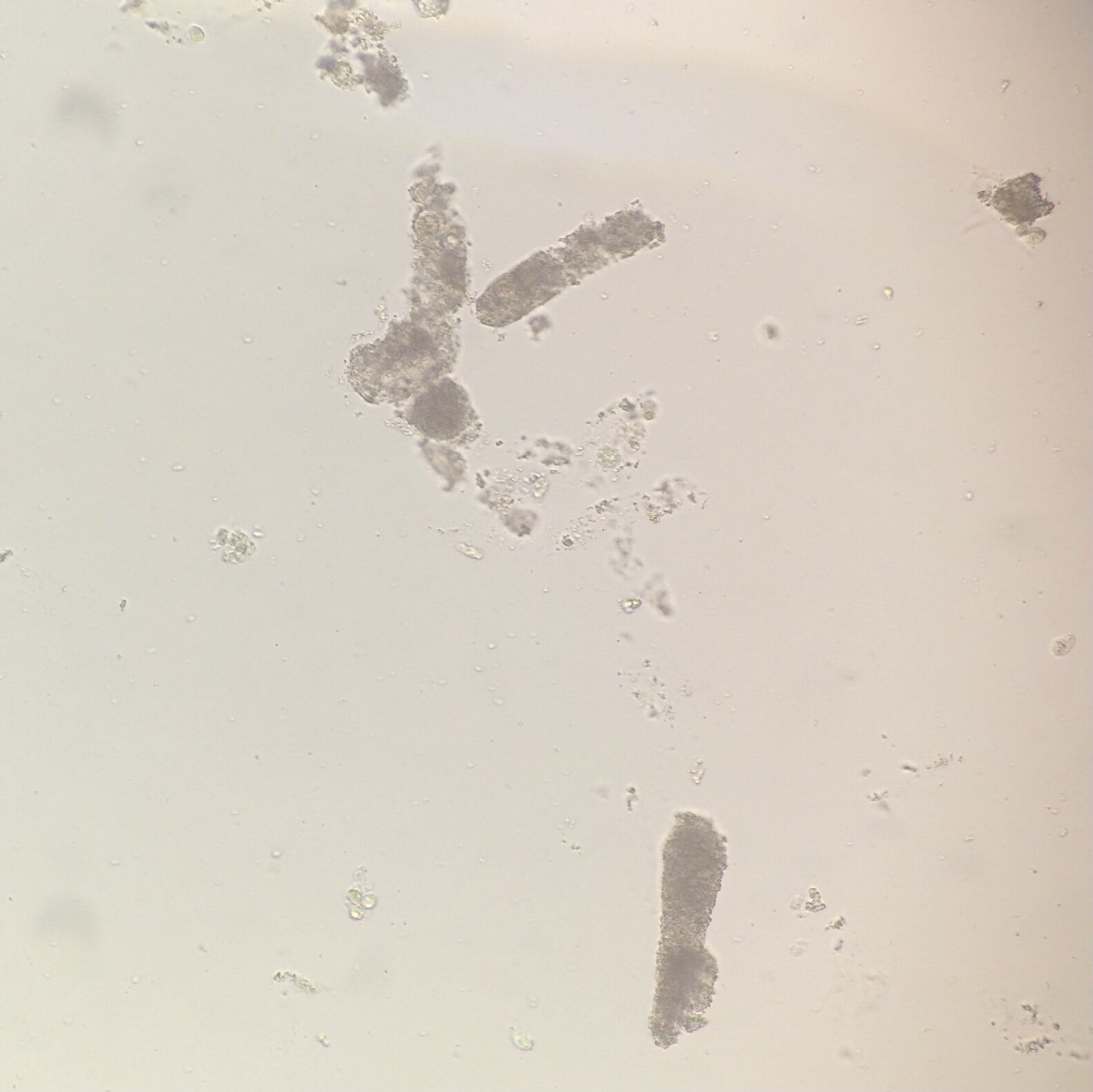

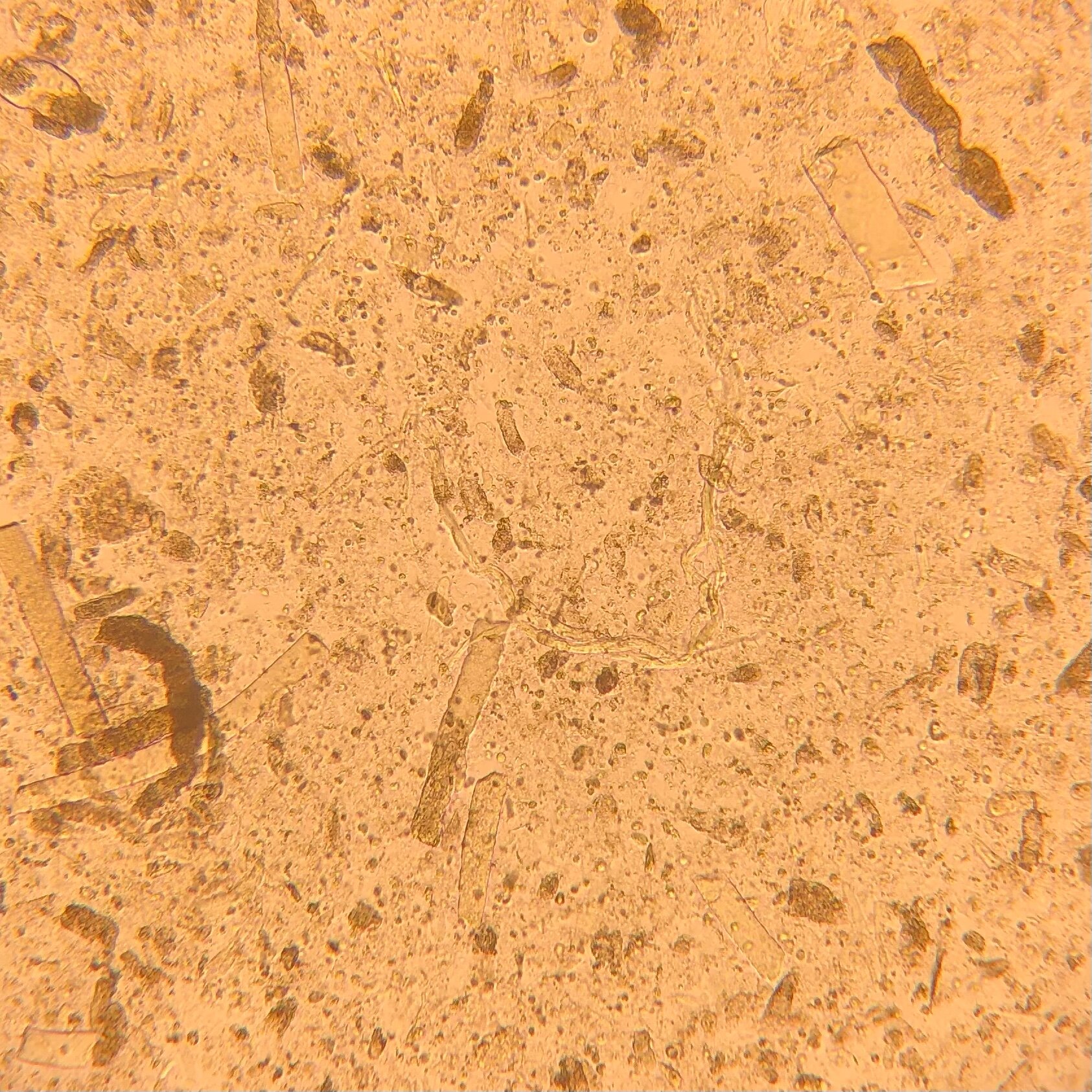

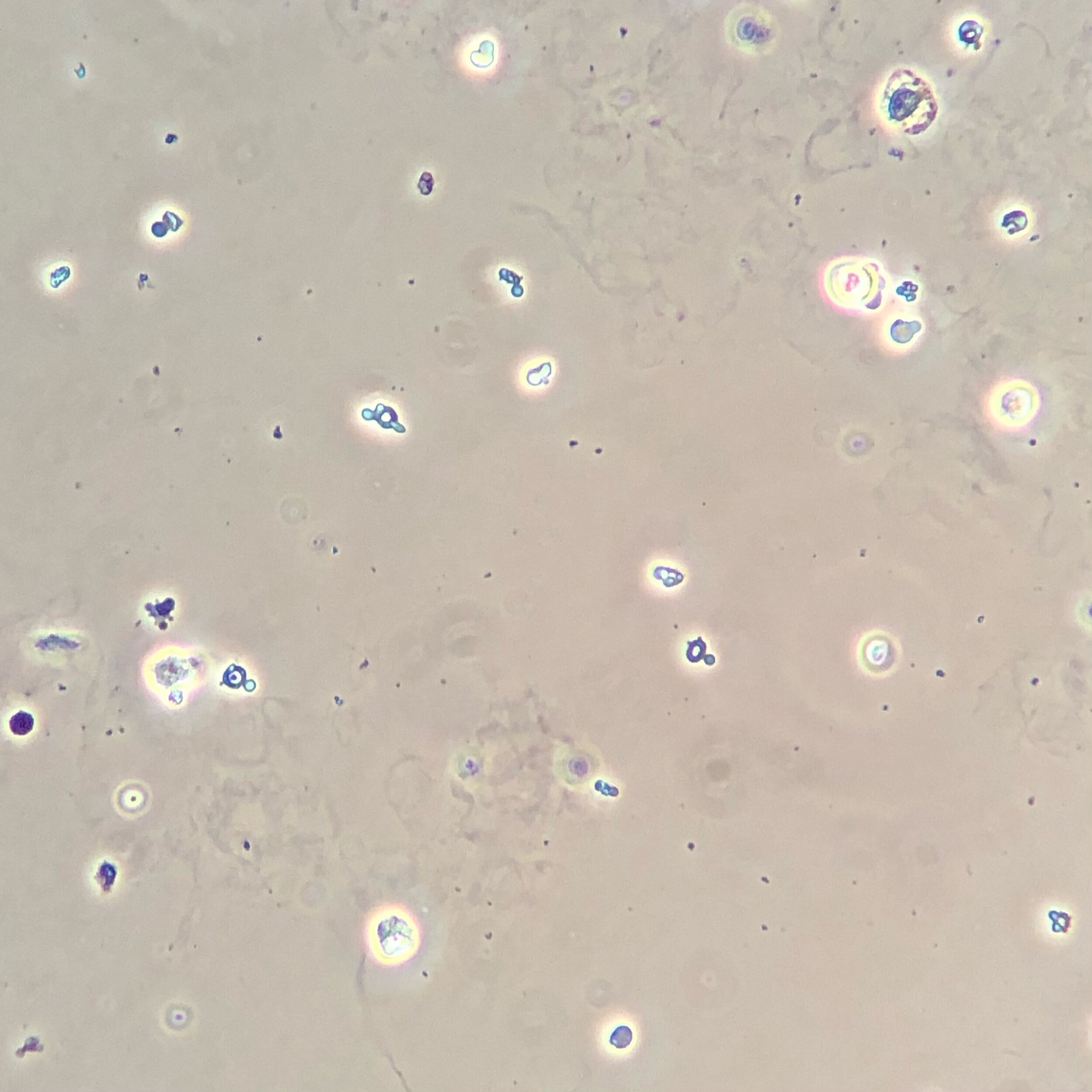

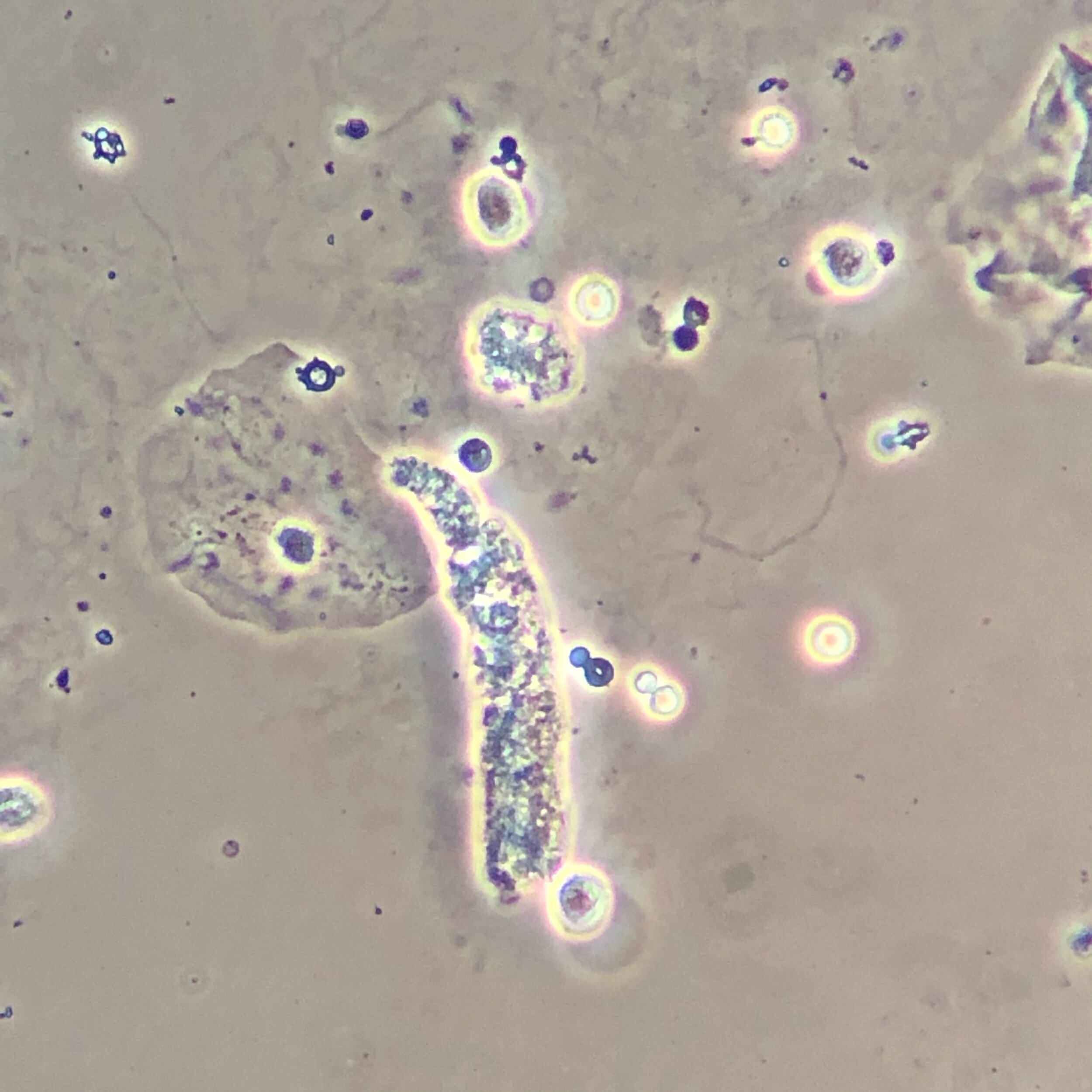

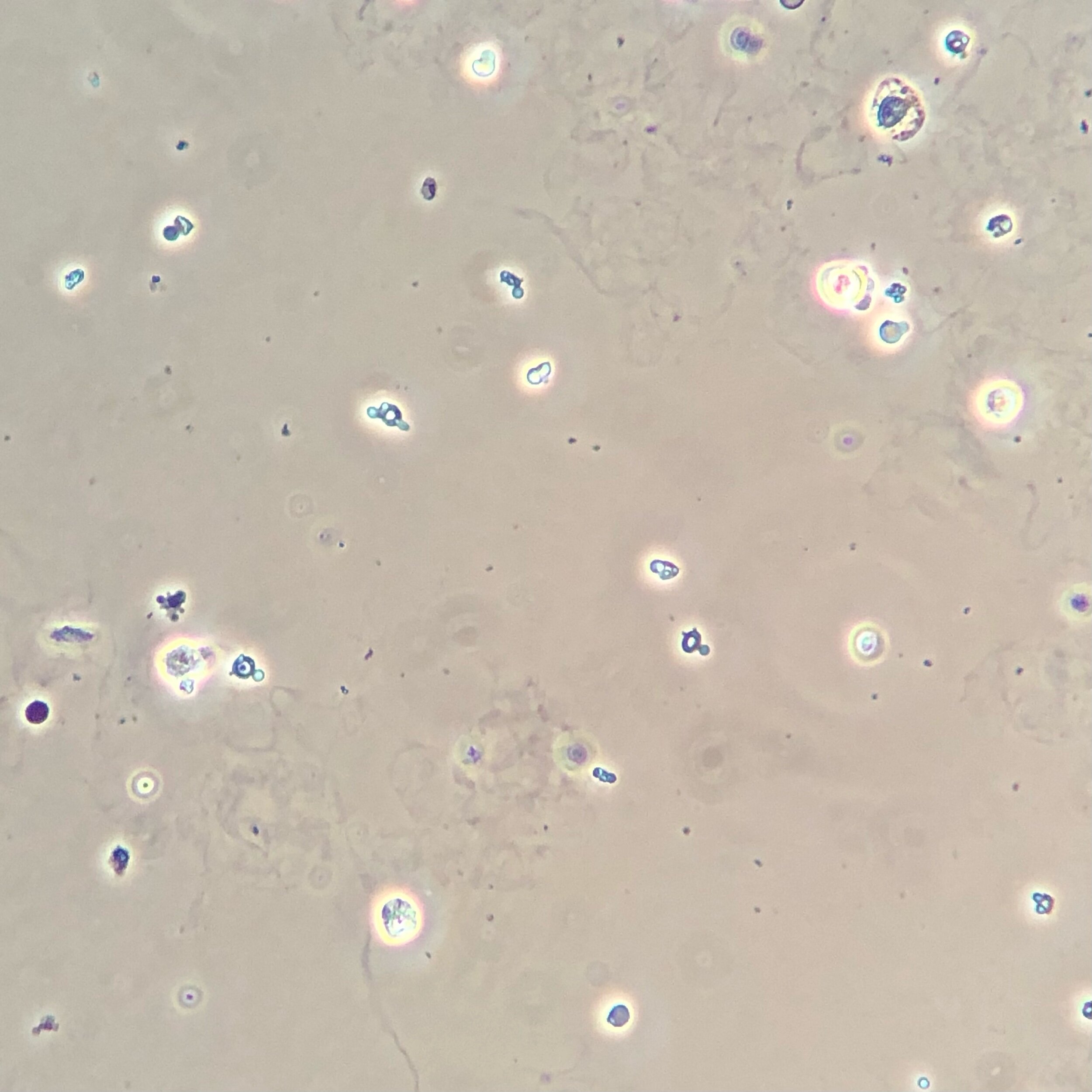

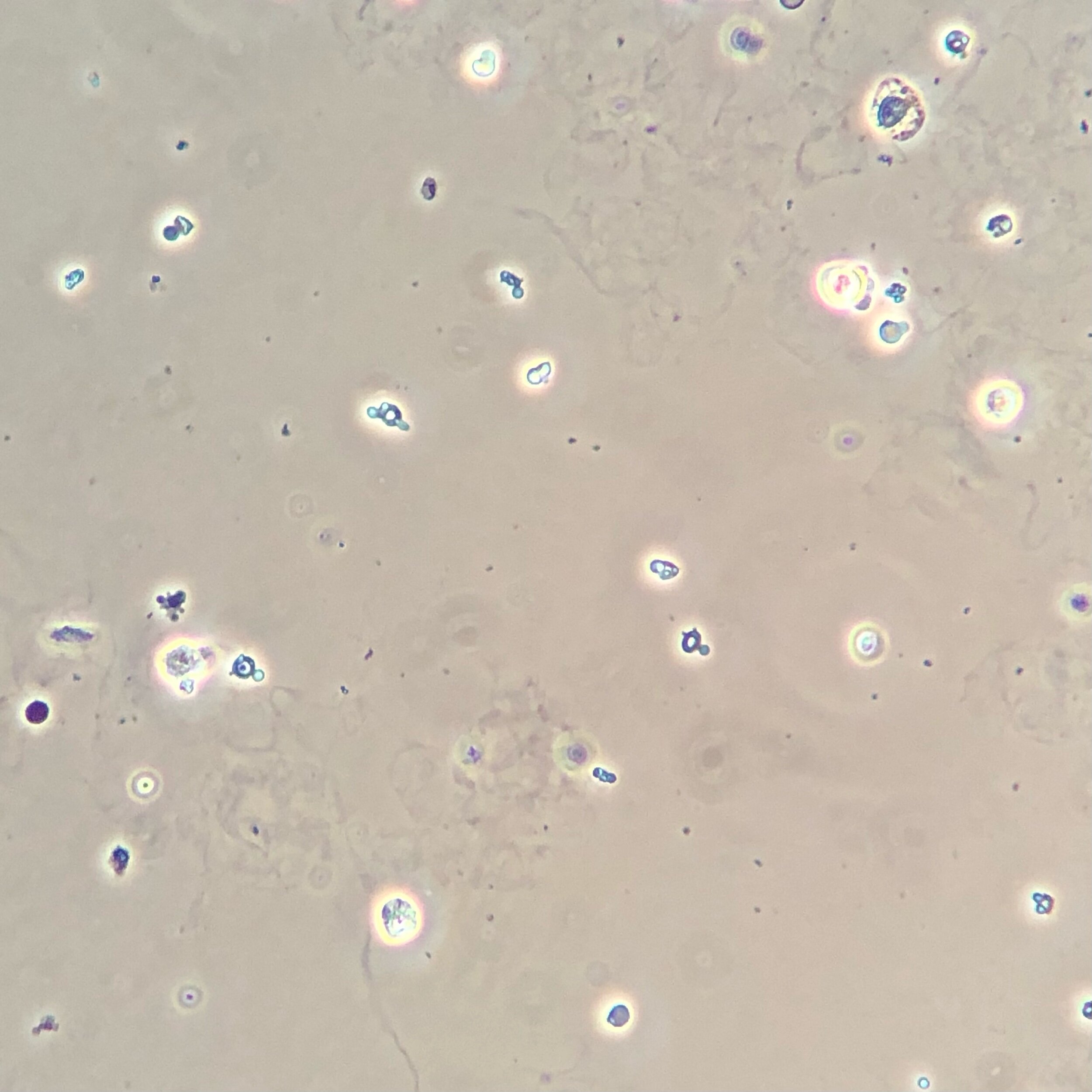

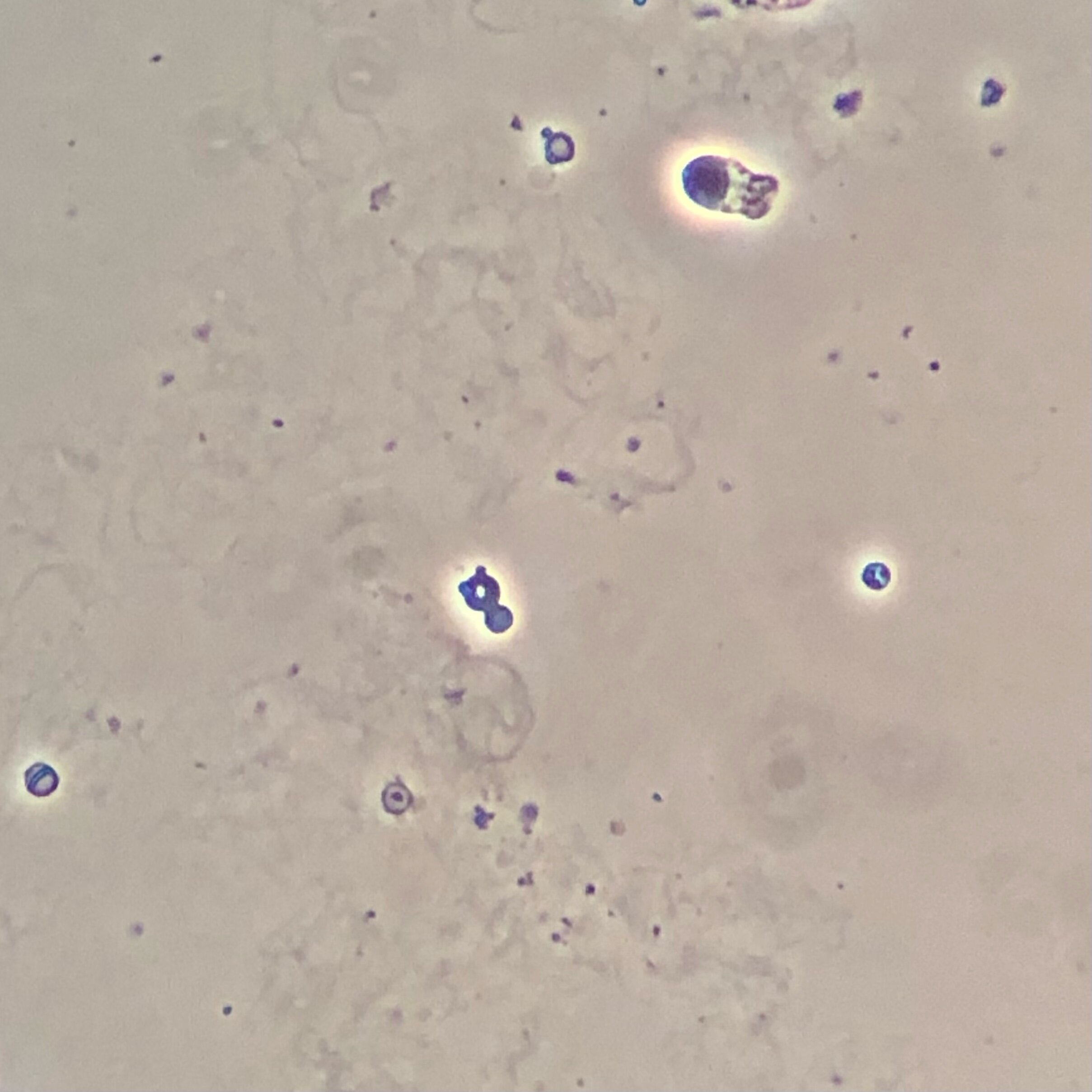

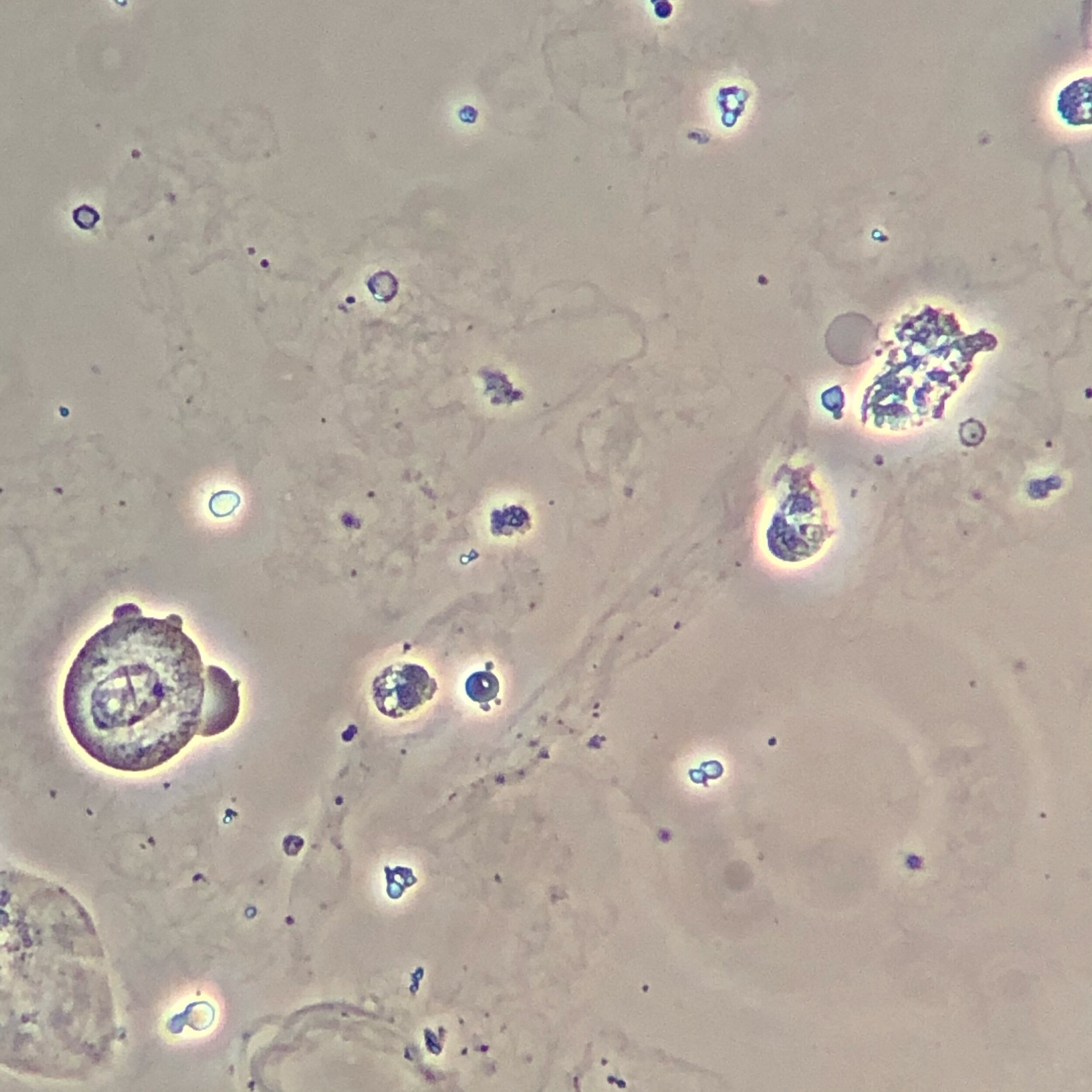

Below are urine sediments containing an overall picture of acute tubular necrosis (ATN).

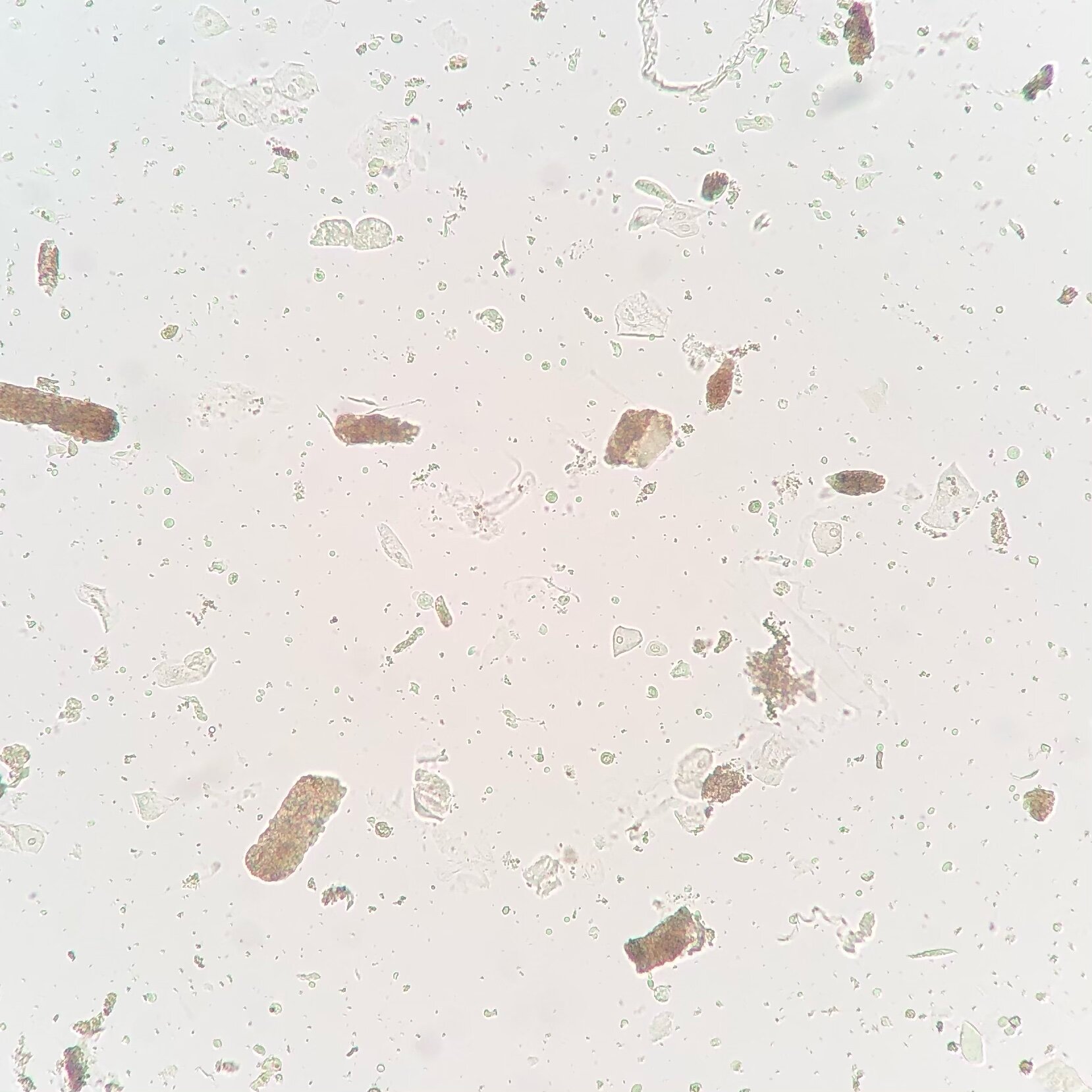

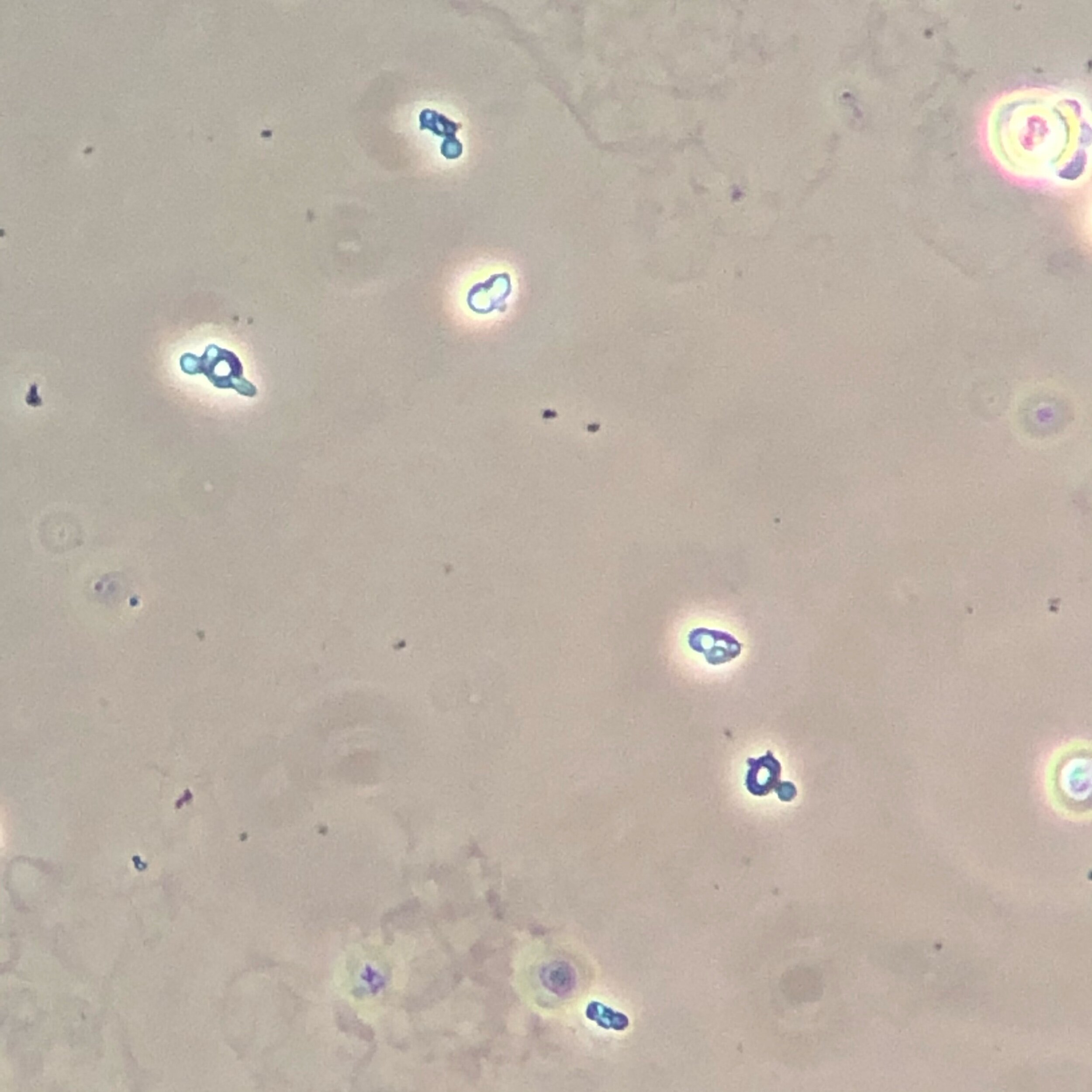

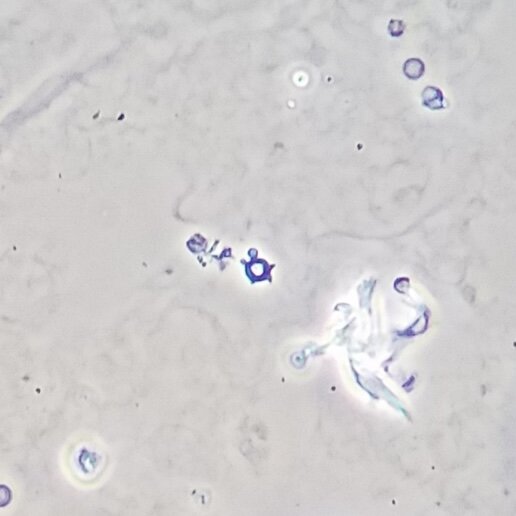

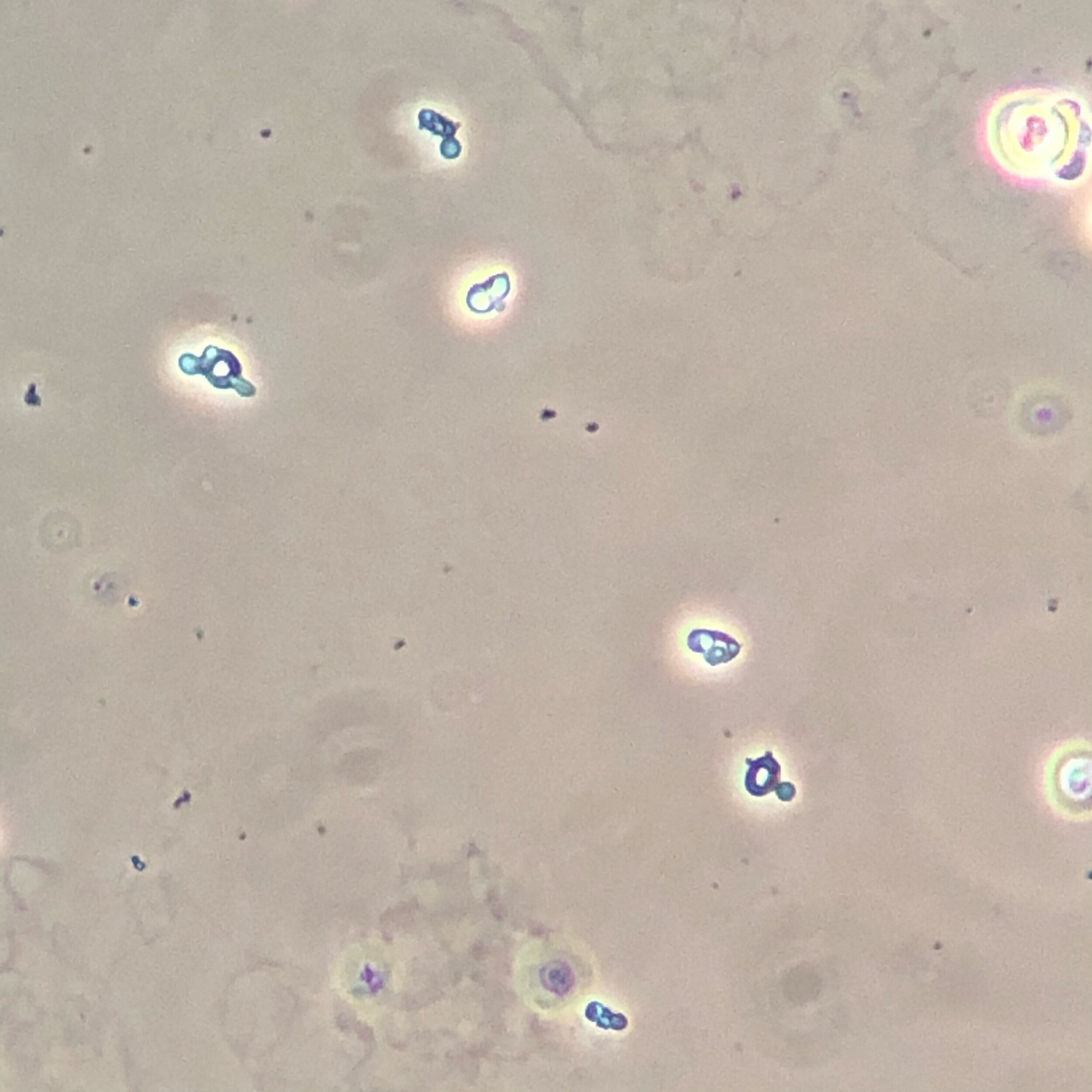

Dysmorphic Red Blood Cells

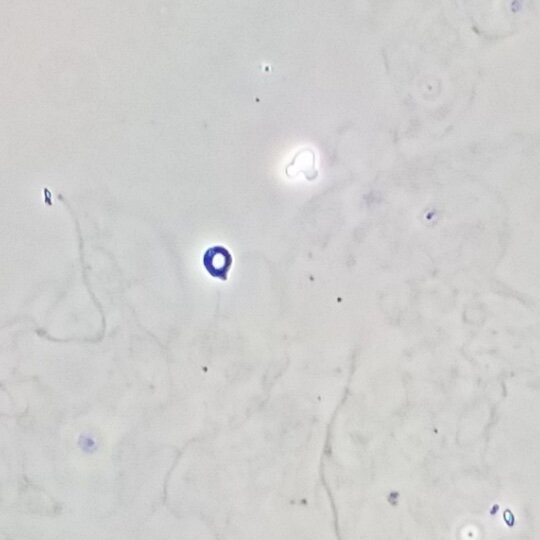

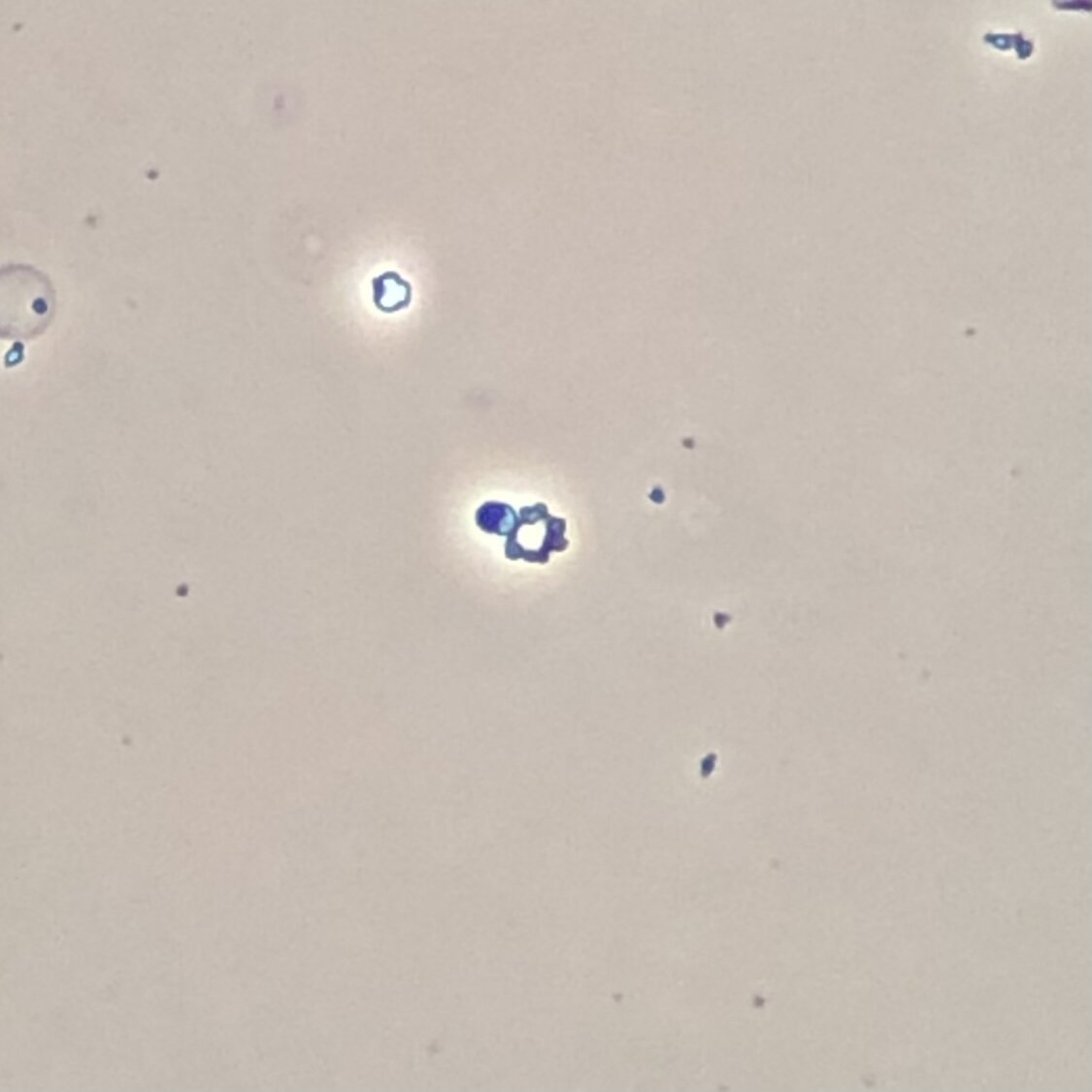

There are several different type of dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs), but the type specific for glomerulonephritis are acanthocytes. These RBCs are misshapen to resemble doughnuts with blebs. Some say they also resemble turtles, but either way, these dysmorphic RBCs below indicate glomerulonephritis.

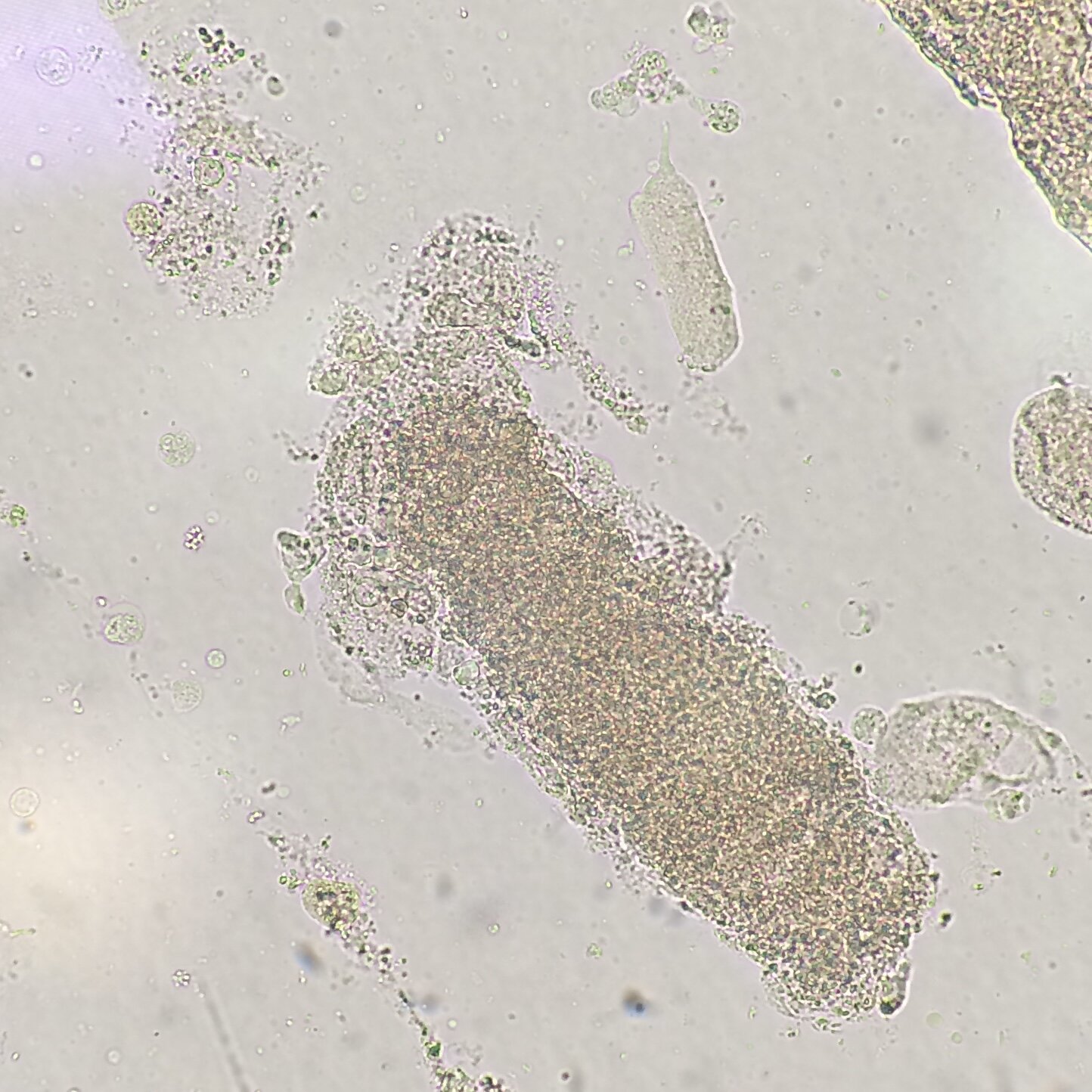

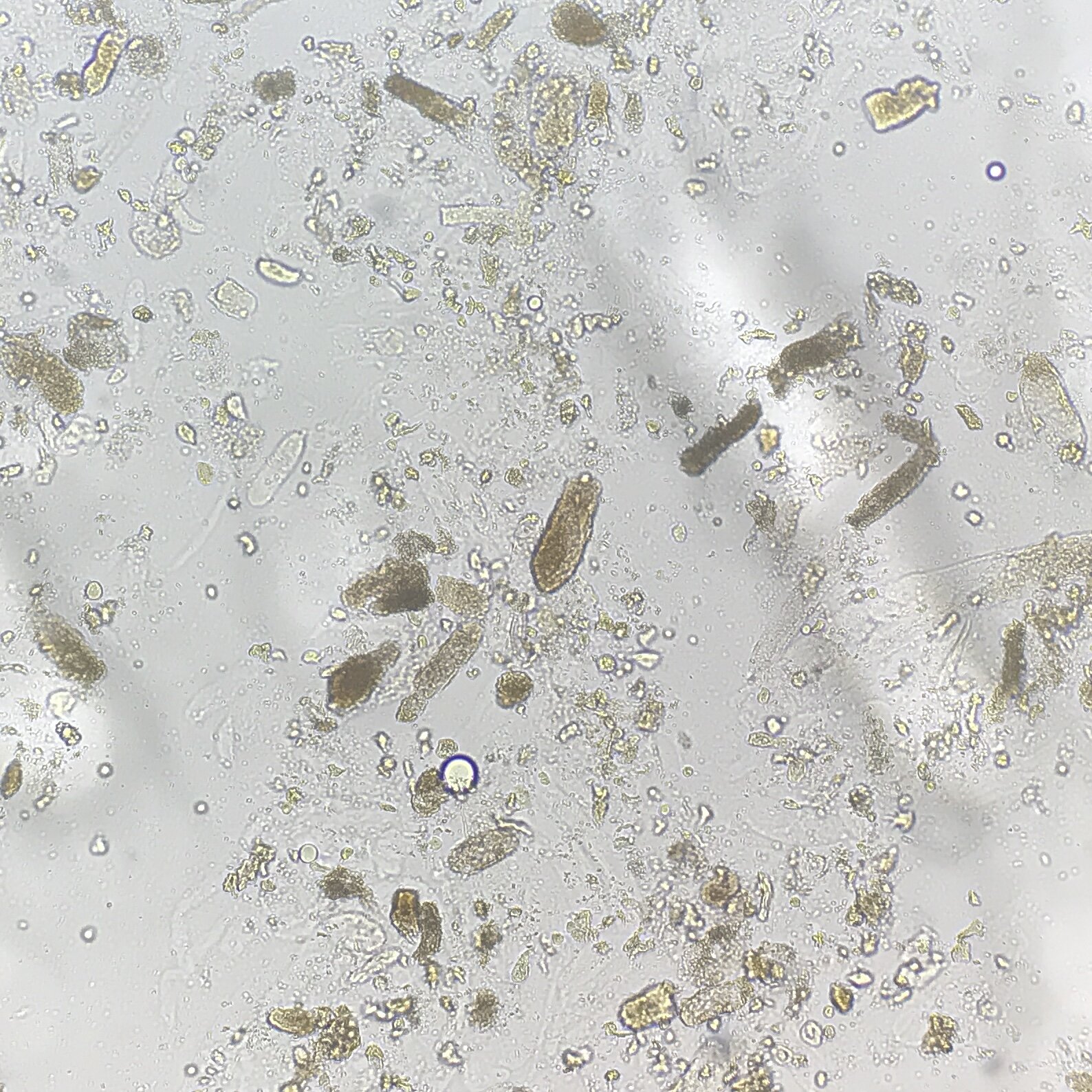

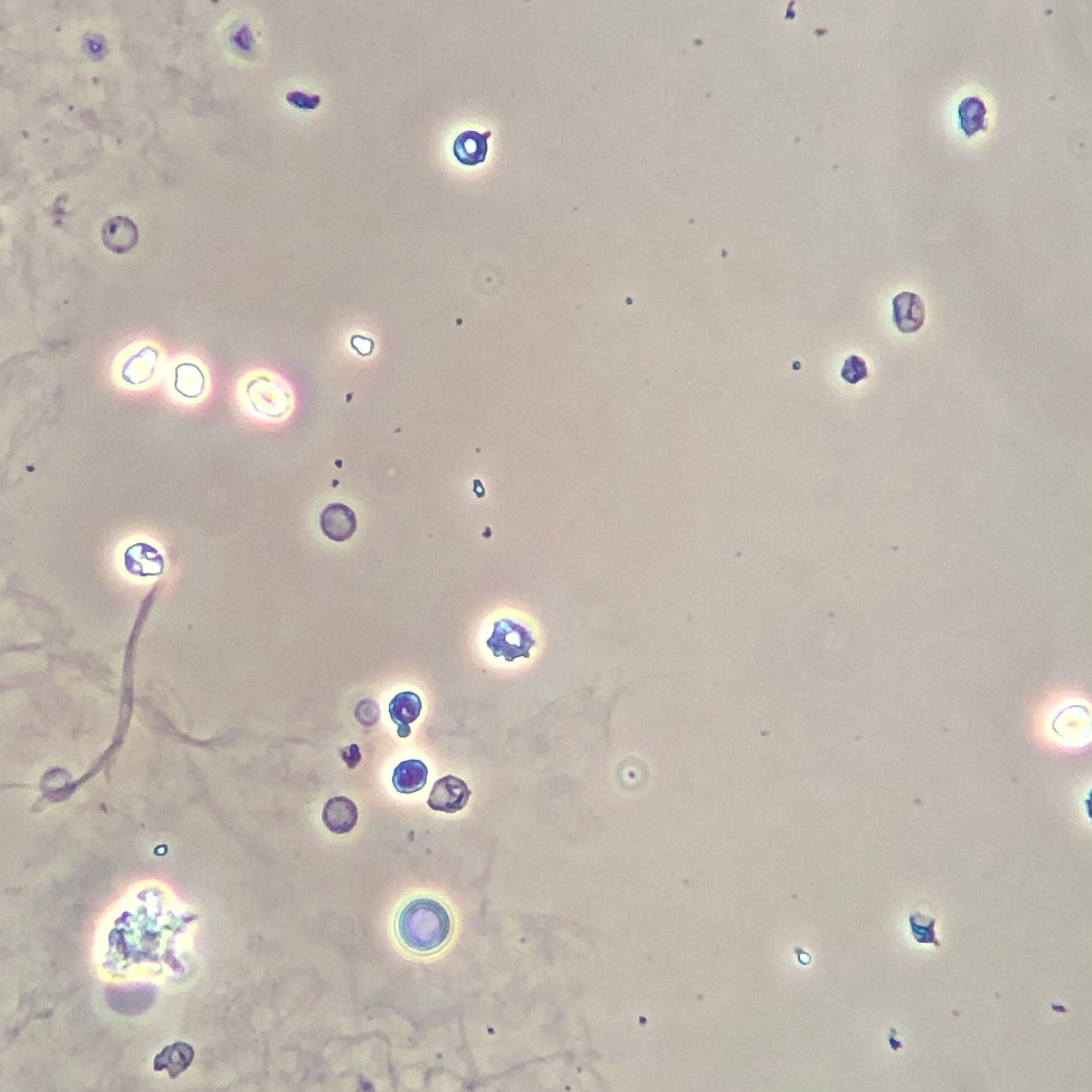

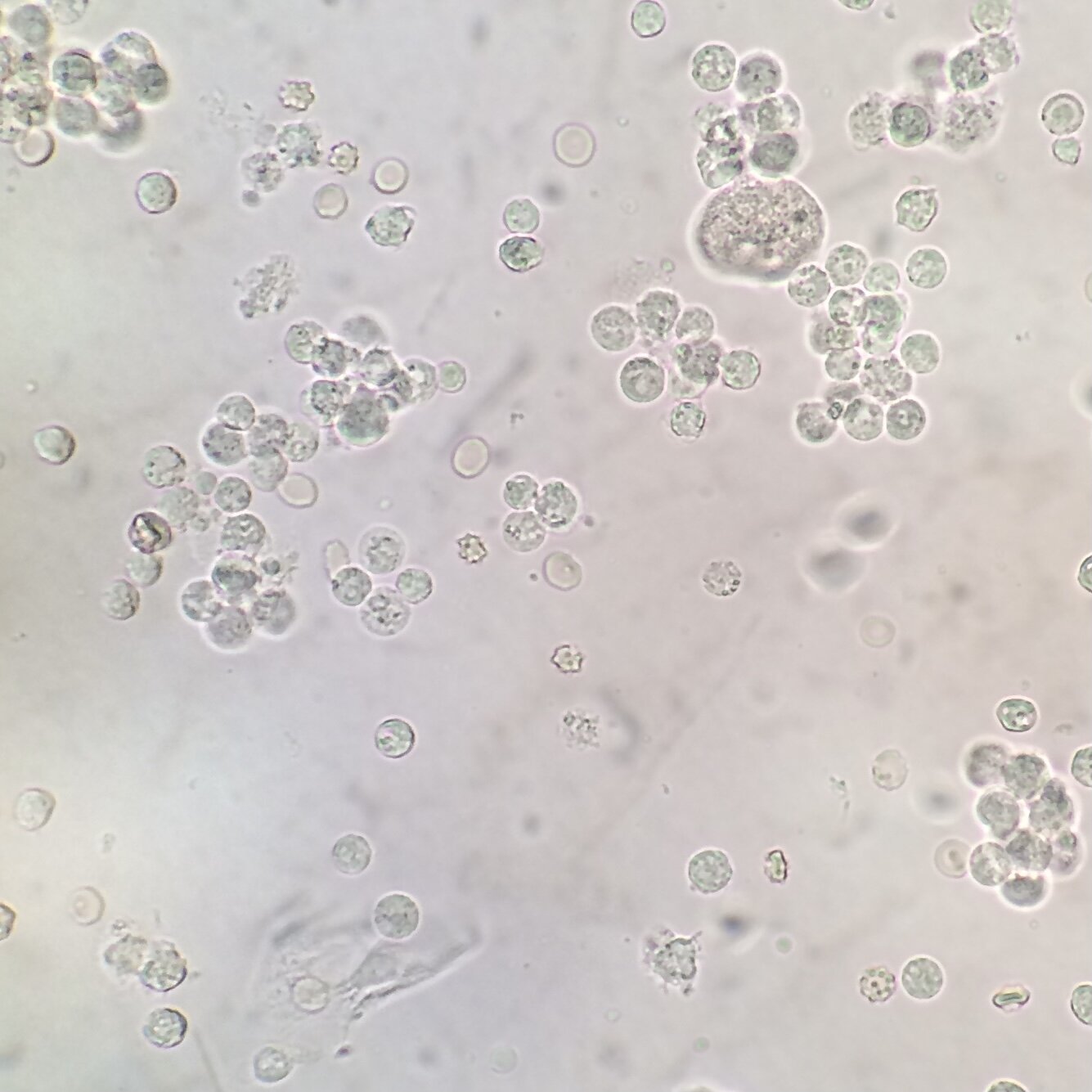

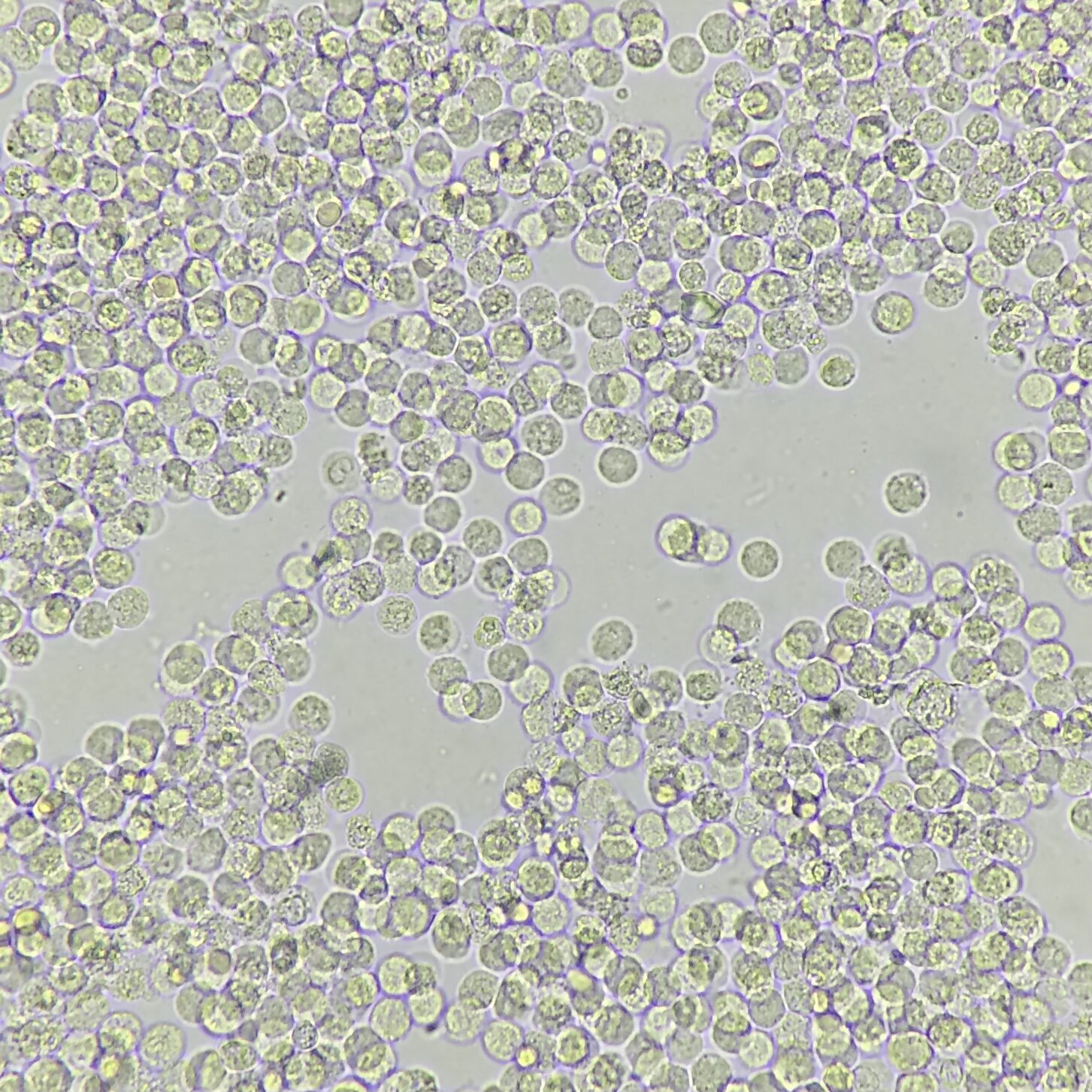

White Blood Cells

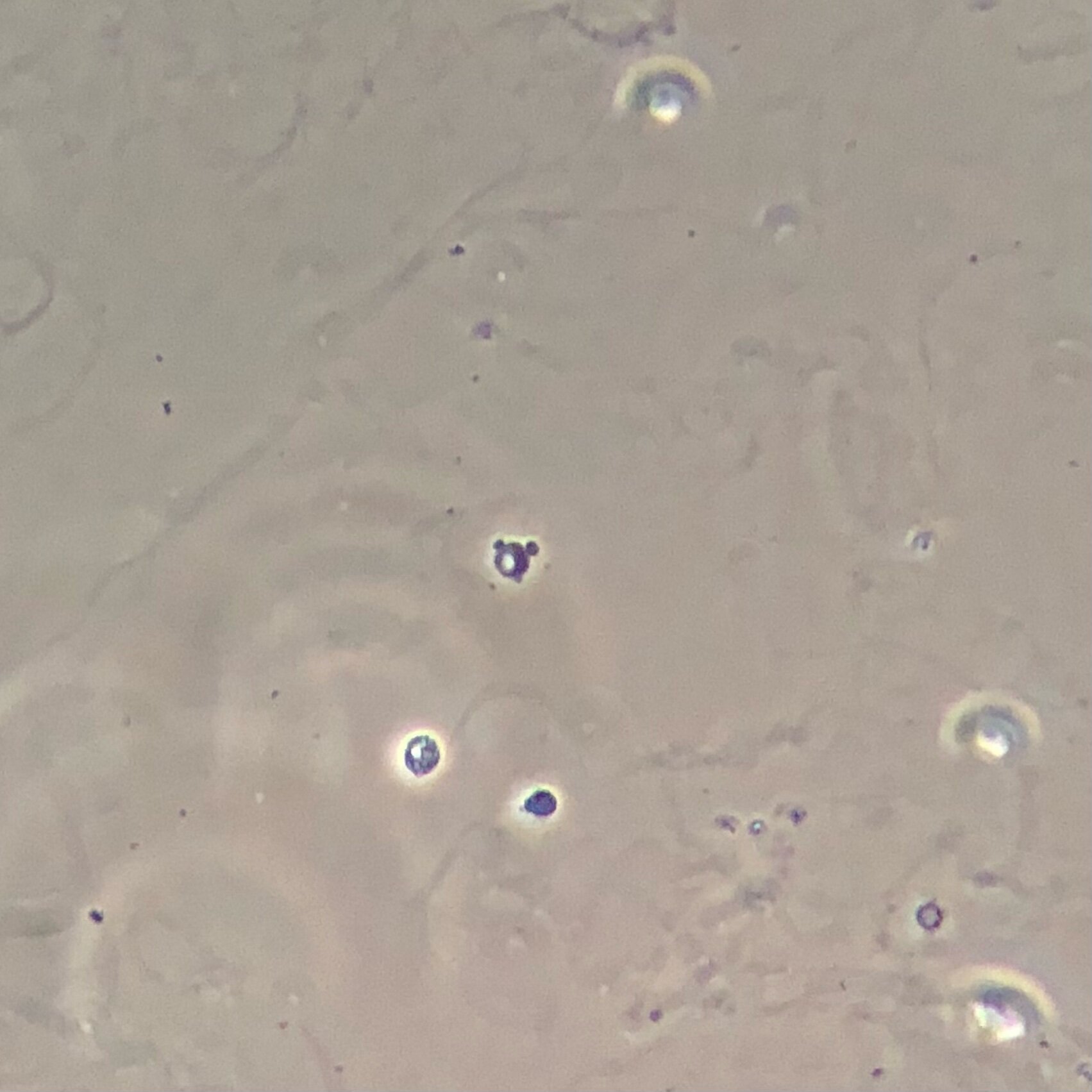

White blood cells (WBCs) most often indicate a urinary tract infection. They are also useful in the event that you see a WBC cast in the setting of negative urine cultures — this is a presentation that can indicate acute interstitial nephritis. In the images below, look for cells (that are larger than RBCs) with a notably granular cytoplasm. If you are trying to find a WBC cast, look for cylindrical structures which include WBCs encased within the cast itself.

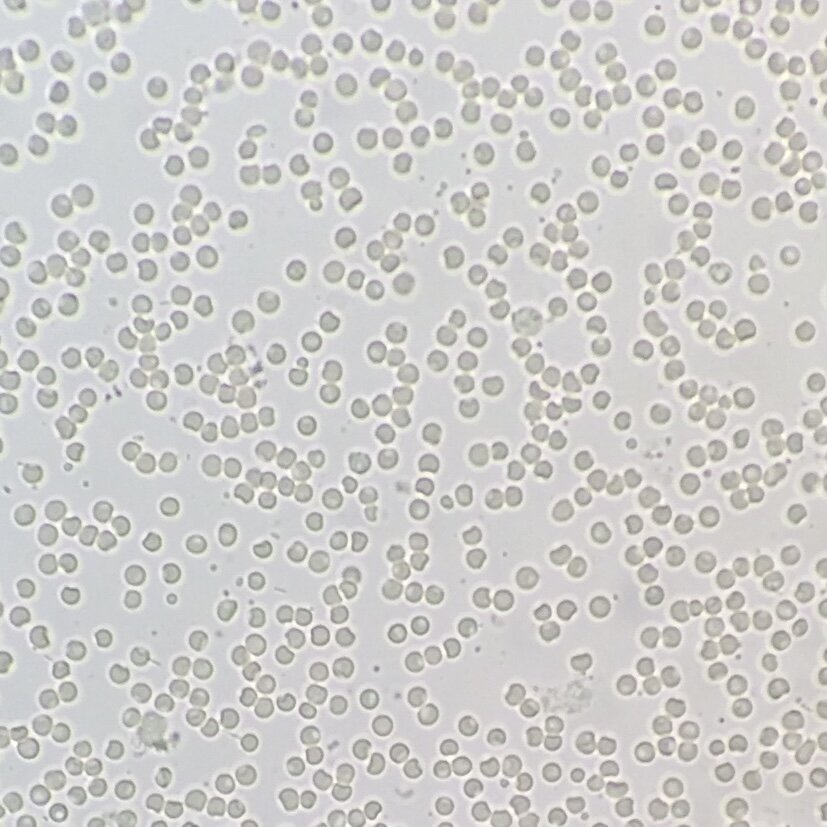

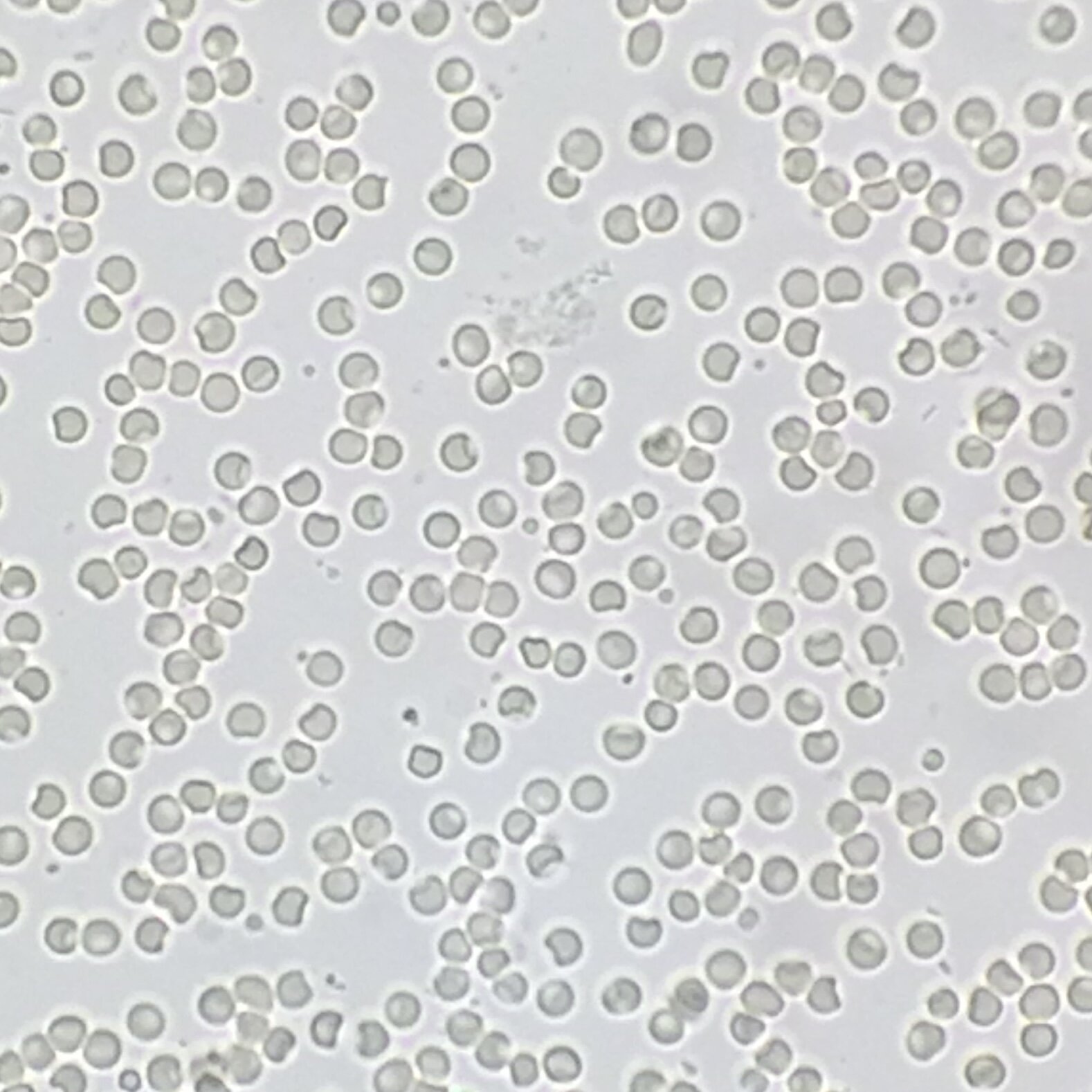

Monomorpic Red Blood Cells

Monomorphic RBCs are simply RBCs which are not misshapen and do not indicate glomerulonephritis. These cells end up in the urine due to trauma in the urinary tract (such as kidney stones, foley placement, ect) and can also increase in quantity due to patient’s being on anticoagulants.

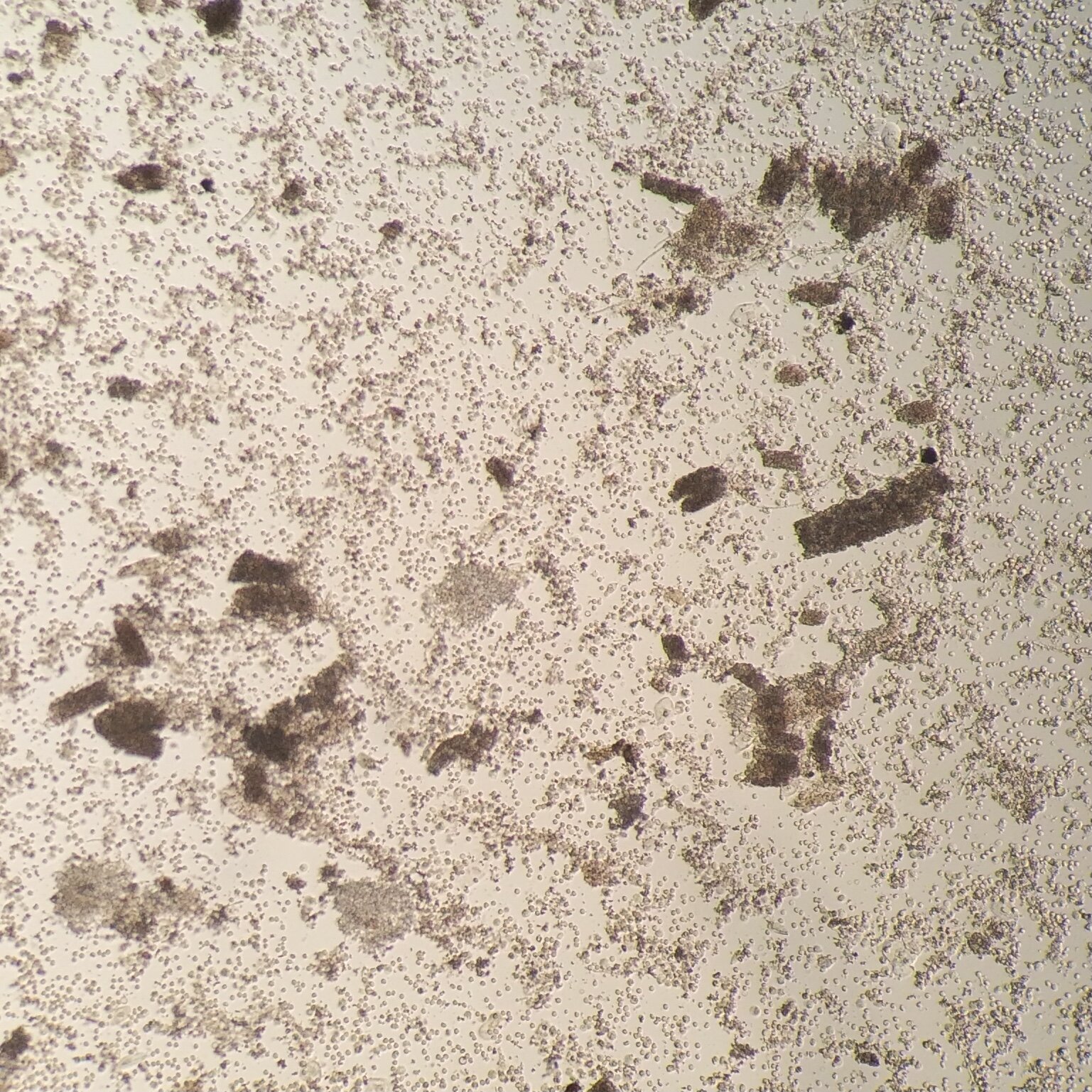

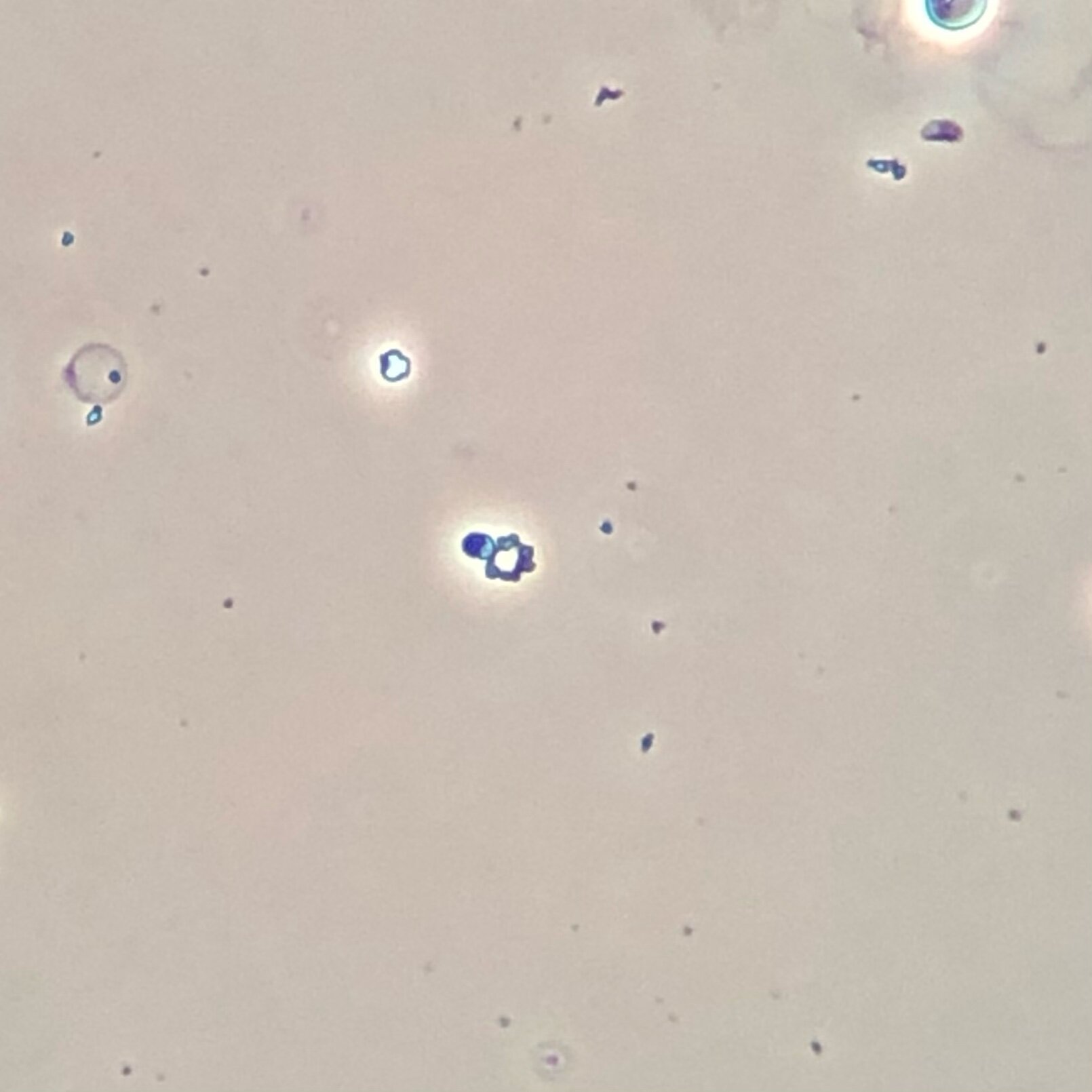

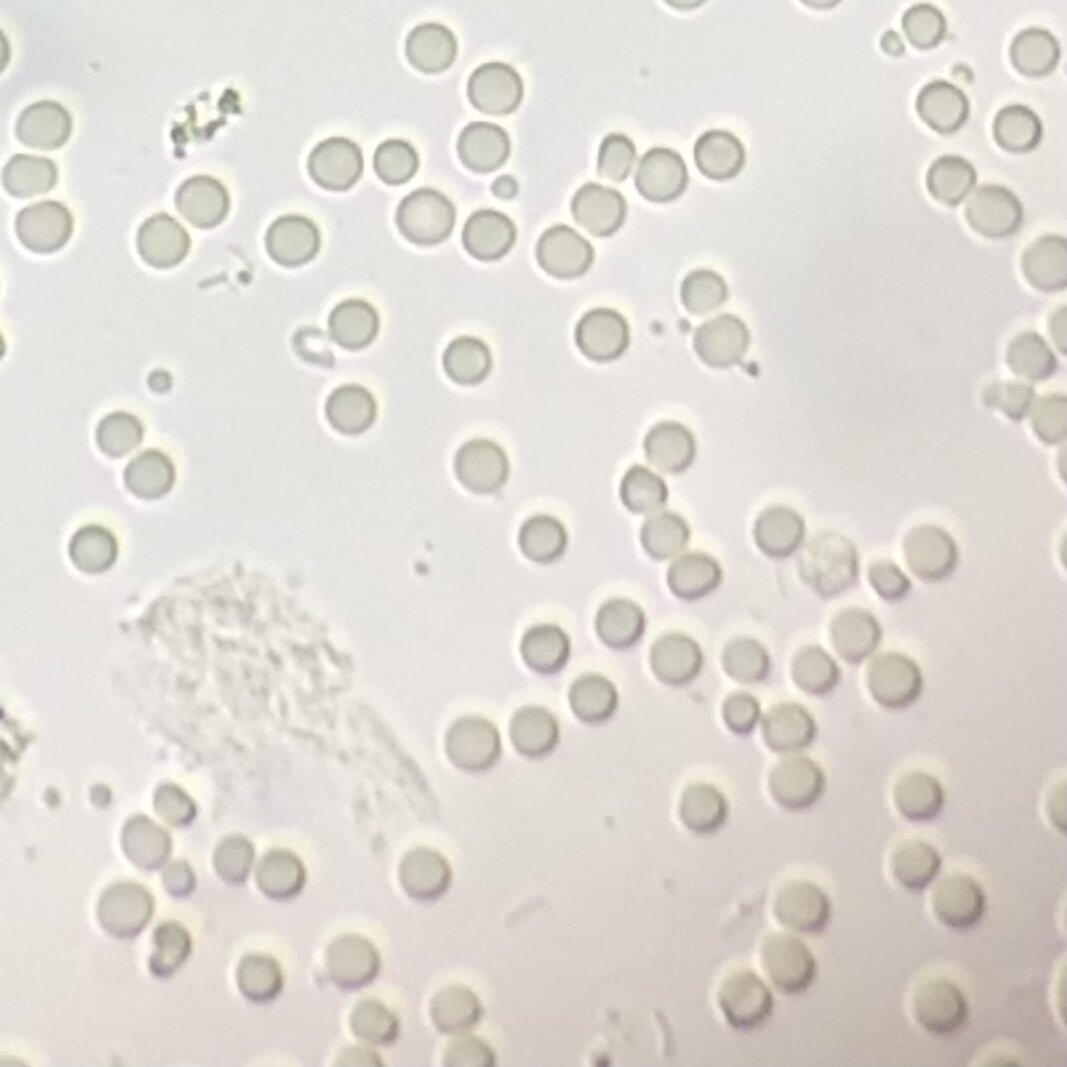

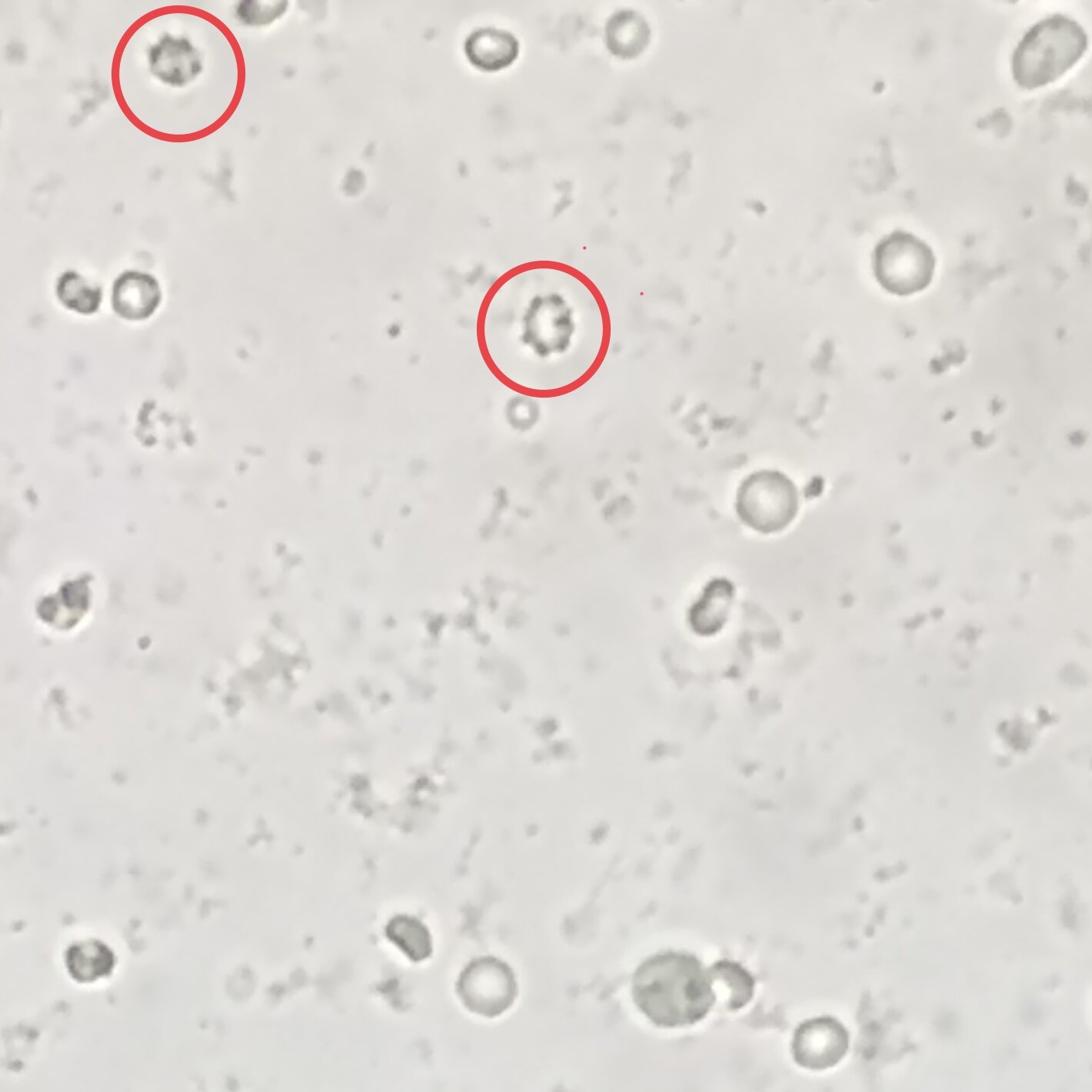

Crenated Red Blood Cells

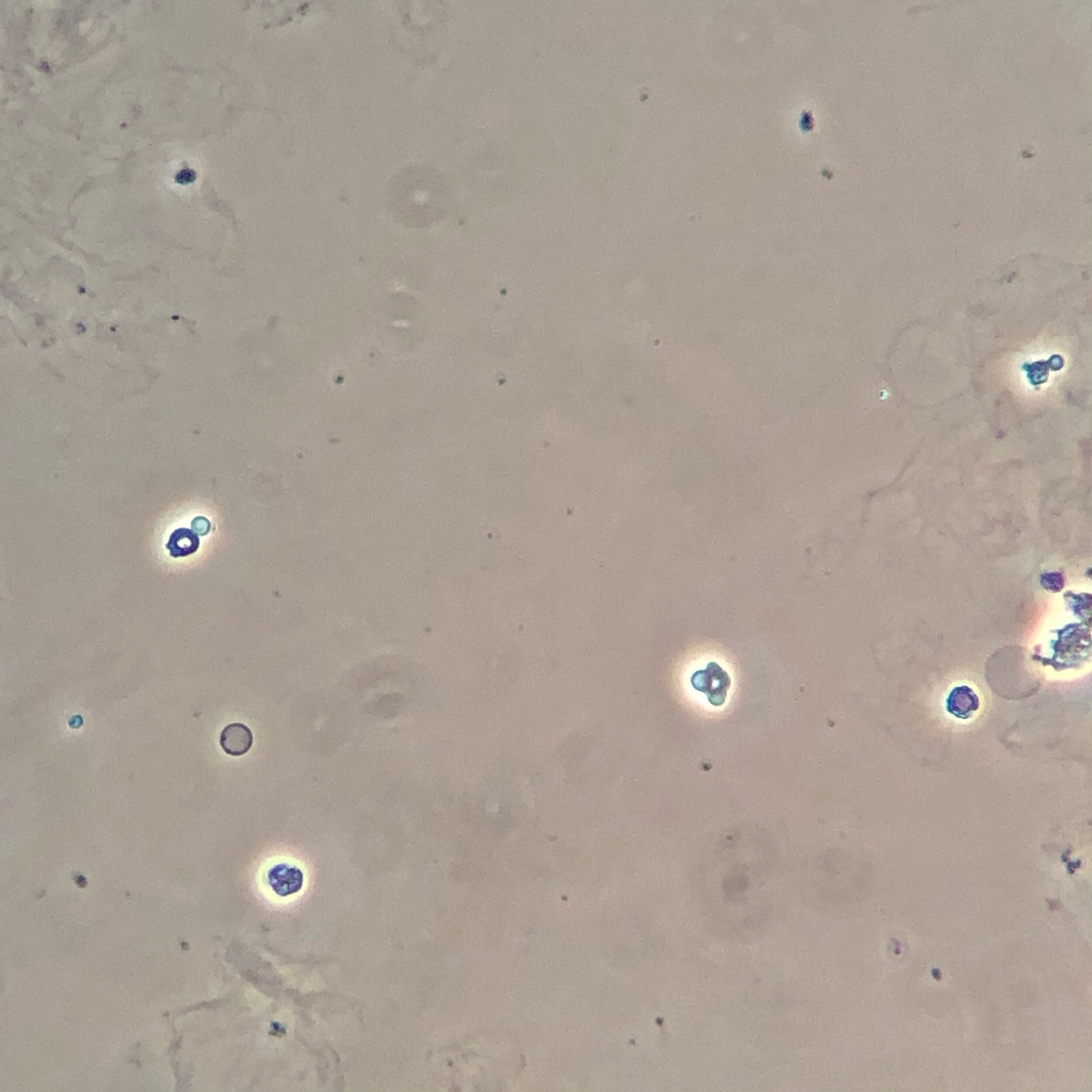

Crenated RBCs are monomorphic RBCs that have been sitting in urine for a prolonged period of time. The resulting osmotic stress on the RBC membrane causes small spikes to form on the RBC membrane. These spikes are not as pronounced as acanthocyte blebs and importantly, the characteristic doughnut shape of acanthocytes is missing from crenated RBCs. Look at the images below to see creanted RBCs denoted by red circles.

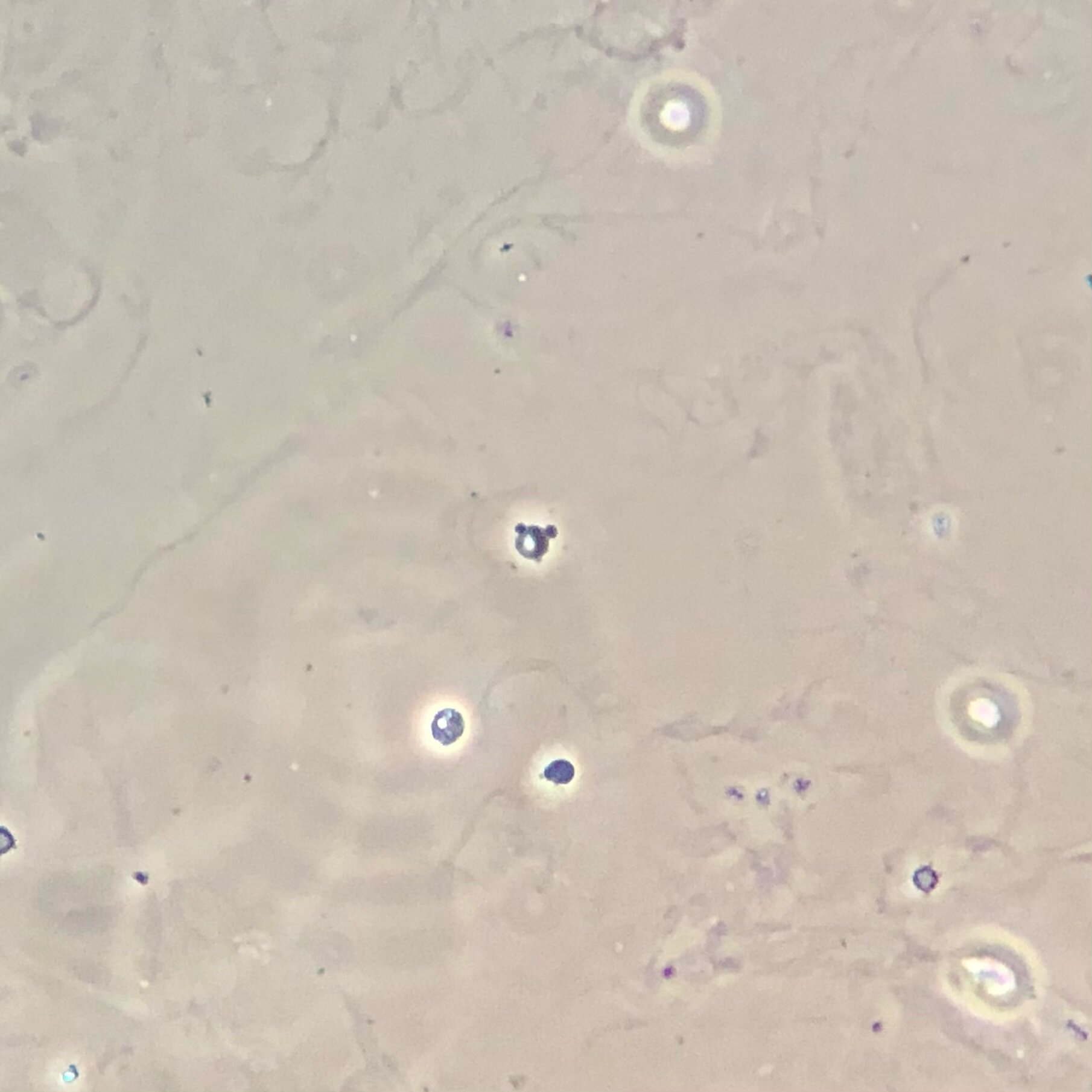

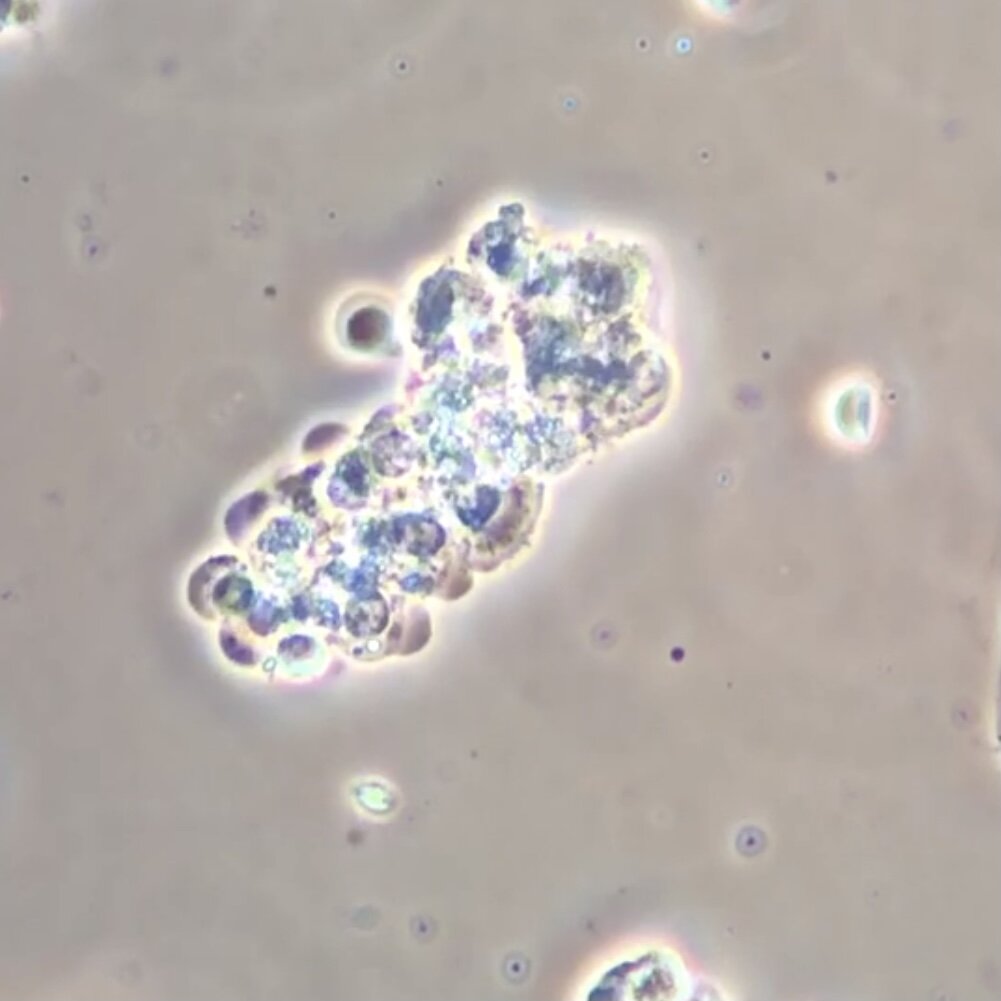

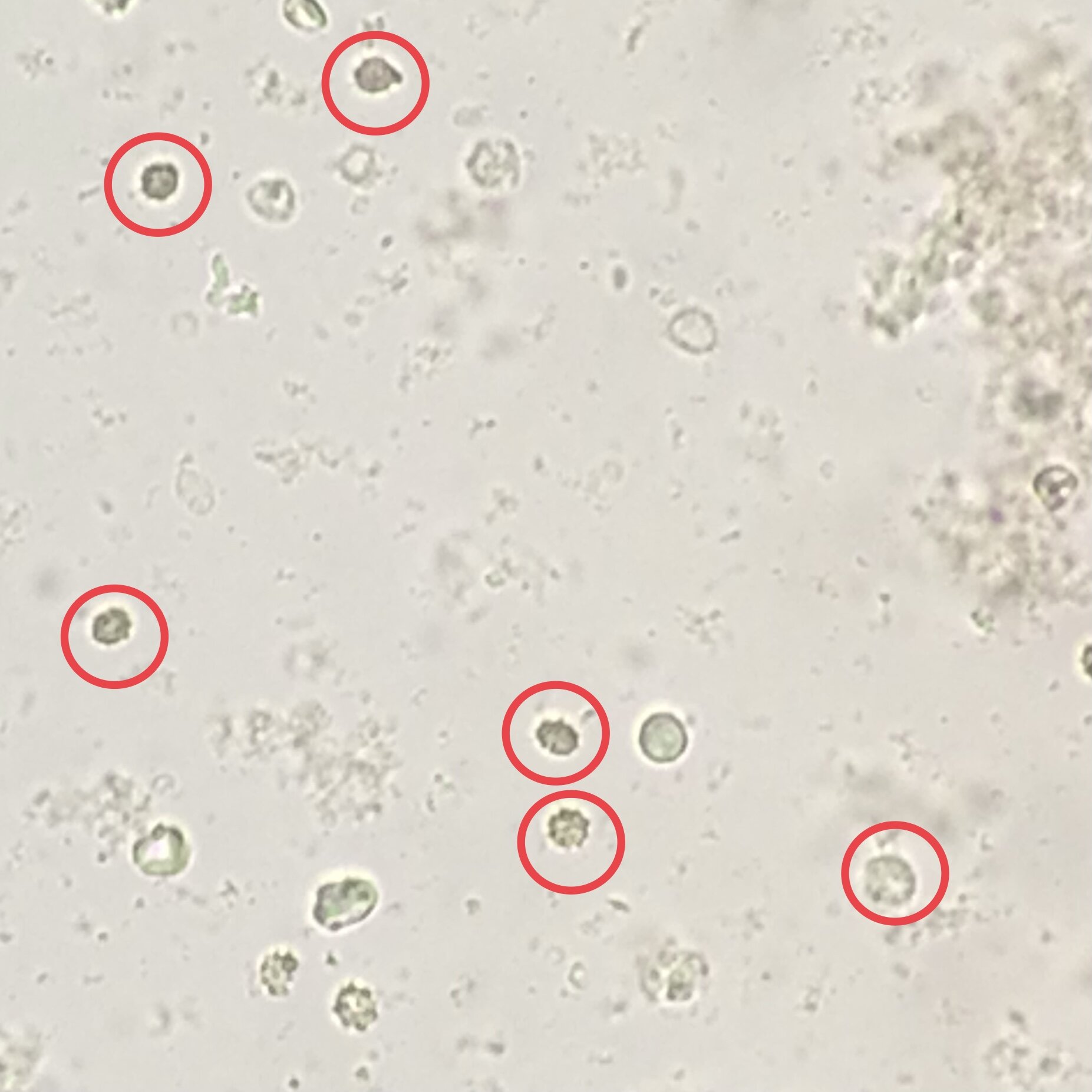

Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells

We commonly use the term “acute tubular necrosis” or “ATN” to describe a process which actually involves either necrosis or apoptosis of the renal tubular epithelial cells that line the nephron. Although “ATN” suggests that all RTE cells undergo necrosis, these RTE cells can either undergo necrosis, apoptosis, or can even slough off into the urine completely intact. In this last scenario, we can even see intact RTE cells in the urine. Look at the images below to see RTE cells denoted by red circles. To distinguish an RTE cells from a WBC, look at the nucleus. An RTE cell will have a large, eccentrically-placed nucleus.

Additional Reading

To become a true pro at urine microscopy, read these articles from the Renal Fellow Network on urine sediment analysis as well as open source articles on the urine sediment from AJKD.

Gross inspection of the urine:

https://www.renalfellow.org/2019/11/06/urine-sediment-of-the-month-the-visible-sediment/

Hyaline casts:

Granular Casts:

https://www.renalfellow.org/2019/04/30/urine-sediment-of-the-month-granular-muddy-brown-casts/

Identifying dysmorphic RBCs:

WBC casts:

Identifying nucleated cells:

https://www.renalfellow.org/2020/07/13/urine-sediment-of-the-month-4-flavors-of-nucleated-cells/

Renal tubular epithelial cells:

https://www.renalfellow.org/2018/11/30/urine-sediment-of-the-month/

Crystals:

https://www.renalfellow.org/2019/07/10/urine-sediment-of-the-month-common-crystals/

AJKD Core Curriculum Articles on Urine Sediment:

https://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272-6386(18)30873-4/fulltext

https://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272-6386(08)00584-2/fulltext

Quiz Questions

1. What’s the oldest (in hours) we can allow urine to be if we are going to spin it?

2. What disease process (i.e. etiology of AKI) is suggested by a WBC cast in the presence of negative urine cultures?

3. What cell is this?

4. What disease process is represented here?

AKI Workup

Evaluating a patient for AKI comprises the majority of consults we see in the hospital. To get a handle on this, read the AKI Evaluation overview here. To help you organize thoughts, we have created a worksheet to assist with AKI evaluation. Download this sheet by clicking the button below and use it on your next AKI evaluation.

For extra points, take a look at the open source article listed below and then test your knowledge with the interactive AKI cases at NephSim

AJKD Core Curriculum AKI Management Review Article

NephSim Interactive Cases

Quiz Questions

What are the 3 diagnostic criteria for AKI (two are changes in serum Cr and one is a change in urine output)?

Name 3 medications that can cause AKI.

What is the triad associated with acute interstitial nephritis?

What disease process should you always consider if a patient has AKI and thrombocytopenia?

What disease process should you consider if someone has AKI or worsening kidney function in the setting of hypercalcemia, anemia, and maybe a low (or negative) anion gap?

Does gadolinium-based MRI contrast cause AKI?

Hospital Management of Hypertension

Hypertensive emergency is defined as any condition where elevated blood pressure is accompanied by either target organ damage or some other situation that requires immediate lowering of blood pressure. Hypertensive urgency is defined as systolic pressure >180 or diastolic pressure >110 without evidence of target organ damage. Differentiating between these situations and very elevated blood pressure that is circumstantial (i.e., post op pain) or when reduction is actually hazardous (i.e., post atherosclerotic/embolic stroke) is imperative to ensure proper treatment and patient safety (Kaplan, 2018). Approximately 1-3% of patients with hypertension will experience a hypertensive emergency in their lifetime (Benken, 2018), making it a rather rare phenomenon. In regards to hospital presentations, hypertensive emergencies account for about 25% of hypertensive associated crises. Whereas, hypertensive urgency makes up roughly 75%.

Symptomology of hypertensive emergencies may include headache, visual disturbance, GI symptoms, encephalopathy, renal impairment, and rarely microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA). Appropriate history and physical exam findings can often give large clues as to why the blood pressure is elevated. It is important to start appropriate screening for other potential causes such as illicit drug use, medication noncompliance (this is a BIG one), and to consider possible secondary causes - particularly renovascular hypertension - during the initial evaluation.

Hypertensive emergencies require immediate intervention which includes establishing IV access and initiation of intravenous antihypertensives. Patients should be monitored closely, preferably in the intensive care unit. Which parenteral drug is selected for treatment should be based on clinical findings and patient history. (See table). Target blood pressure for patients in hypertensive emergency is based upon etiology. For example, in the event of retinal hemorrhage, microangiopathy, or acute renal failure the mean arterial pressure should be lowered 20-25% over several hours. However, with situations such as aortic dissection or pre-eclampsia, target blood pressure should be achieved as quickly as possible (see table).

After the acute phase is over, evaluation should continue for potential secondary causes if that work up has not been completed and transition from IV to oral therapy should start.. It should be anticipated that most patients with hypertensive emergencies will require multiple oral medications to maintain control. Compelling indications for specific drugs should help guide the decision of treatment (diabetes and heart failure - think ACE/ARB, anxiety - think beta blocker, and so on…). Blood pressure variability is expected in the acute care setting because blood pressure is a constantly changing biometric that is influenced by experiences and emotions. A single isolated reading should neither confirm nor negate effective management. Rather, the overall trend of the blood pressure should be used to determine appropriate medication titration and response.

Asymptomatic hypertensive urgency is a problem that is frequently encountered in the acute care setting. The most recent studies show that management of asymptomatic hypertensive urgency is actually better suited for outpatient management than when treated in the emergency room or inpatient setting. Optimization of oral medications, using combination therapies when able, and ensuring that there are no barriers to obtaining medications (financial, lack of access, etc) is the name of the game here. Get them over the acute phase, get them out of the hospital, and understand that close follow up is your best bet at long term blood pressure control.

References

Benken, S. T. (2018). Hypertensive emergencies. Medical Issues in the ICU.

Patel, K. K., Young, L., Howell, E. H., Hu, B., Rutecki, G., Thomas, G., & Rothberg, M. B. (2016). Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA internal medicine, 176(7), 981-988.